The Inkwell (1994), then-22-year-old filmmaker Matty Rich’s sophomore feature, ought to have furthered a career that had been made promising by his 1991 debut, Straight Out of Brooklyn. Instead it was fated as premature farewell from a young director — at whom Spike Lee not-incorrectly rolled his eyes for his boastfulness around not being film school-trained and looking down on those who were — who never again made a movie.

Some of The Inkwell’s flaws make Rich’s lack of experience and general discernment clear: his difficulty reining in some of the overacting of its star, Larenz Tate, whose attempts at physical comedy sometimes descend into Steve Urkel levels of grating silliness, and a nearly movie-upending conclusion that ickily romanticizes what unequivocally amounts to statutory rape. But it elsewhere can be a pretty likable coming-of-age movie whose lack of much ambition and deep conflict befit its laid-back summertime setting.

It takes place in the 1970s in Martha’s Vineyard, where Brenda (Suzzanne Douglass), her former Black Panther husband Kenny (a very good Joe Morton), and their 16-year-old son, Drew (Tate), are spending a few weeks with Brenda’s sister’s (Vanessa Bell Calloway) family. It’s not a particularly happy occasion for Kenny, who resents the upper-class conservatism so flaunted by hoity-toity brother-in-law Spencer (Glynn Turman) that the latter proudly keeps portraits of Richard Nixon and Barry Goldwater hanging in the living room. (Through Kenny, the movie is reserved about too uncritically celebrating that the beautifully shot section of Martha’s Vineyard the film is set in is majority Black: What about the families that, unlike them, don’t have the financial means and cultural cachet to access something so special?)

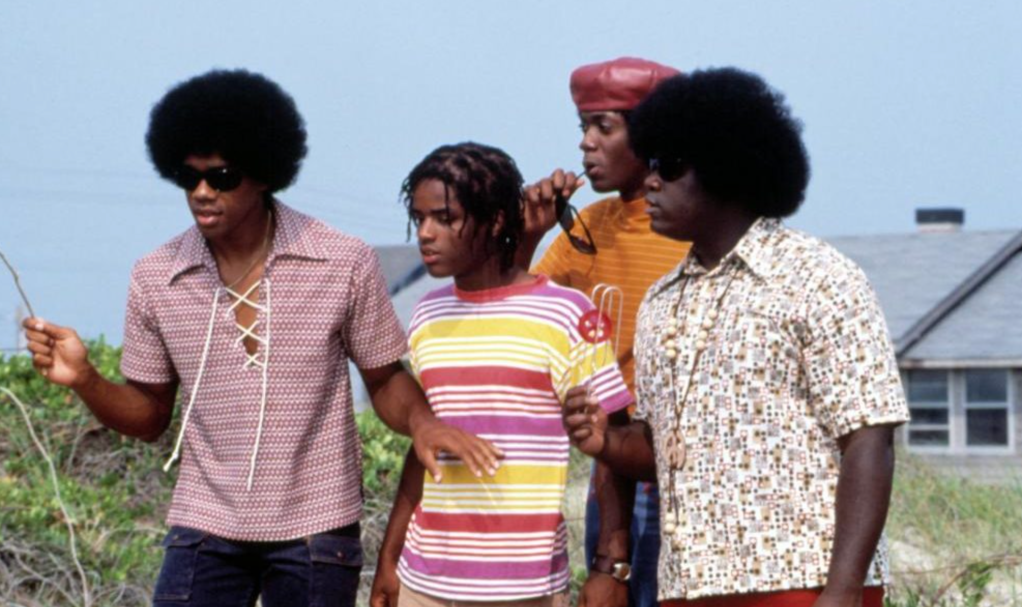

Larenz Tate and Jada Pinkett Smith in The Inkwell.

Kenny and Brenda hope that time away from home will help break Drew out of his shell. He’s so worryingly stuck in it that he has no friends to speak of, save for a wooden doll he’s cobbled together that he talks to as if it could speak back, and eschews socializing in order to hole up in his room making inventions. One memorably includes a contraption that makes a speaker by his bed emit snores if someone barges into his room late at night and he, for whatever reason, isn’t there.

Tate’s performance can be self-consciously dorky, from the way he nervously wiggles his body around to the very way he might wave hello to someone. But you still root for him to come into his own, largely because his father is so vocal in his disappointment with having a son more eccentric than somewhere close to normal. Drew will, impressively, start to rend his needs-to-touch-grass tendencies not by listening too much to his handsome, hard-partying older cousin Junior (Duane Martin), but by following his instincts. They’ll lead him to an all-day date with Lauren (Jada Pinkett), who’s seen by many of her peers as snobbish. The outing serves as the film’s most finely conceived sequence, finding the beauty of a gone-right teenage-years first date’s innocence. (It maintains that by not having it end with a good-night kiss, though the movie’s reason for not including one will be indirectly explained a little later and will throw some water onto the fun that was had.)

How The Inkwell handles another subplot — Drew semi-befriending the wife (Adrienne-Joi Johnson) of a lothario (Morris Chestnut) who doesn’t try to be subtle about his two-timing — is far less successful. That wife will ultimately cross a line in her gratitude for Drew’s eventual airing out of her spouse in a way that’s presented more like a lucky pass into adulthood and not something more sinister. It’s a disappointing narrative decision that lets down some of the sensitivity and perceptiveness shown elsewhere — a sour note for Rich’s foreshortened career to end on.