One could reasonably assume that Crispin Glover’s character in writer-director Trent Harris’ Rubin & Ed (1991) would devour the movie surrounding him. The actor plays the eponymous Rubin with the sort of oddball, all-eyes-on-me bluster with which one has come to associate him. He speaks mostly in brief, usually out-of-pocket exclamations and is styled just like he had been on his now-infamous 1987 appearance on Late Night with David Letterman: with a hastily put-on shoulder-length wig, striped bell-bottoms, and upside-down U-shaped platform ankle boots. (He will a couple times in the movie, like on that late-night show, do perilous high kicks that suggest those shoes could double as a deadly weapon.)

Glover does make an impression in the absurdist road comedy. But it’s more the other guy in this odd-couple movie — Howard Hesseman’s Ed — that leaves the bigger imprint. Glover can wobble into cartoonishness. Hesseman’s sweaty desperation, which he tries to relieve with useless internal repetitions of positive affirmations, is more grounded in the despair real life is so good at doling out.

Howard Hesseman in Rubin & Ed.

The source of middle-aged and helmet-toupéed Ed’s suffering is the demise of his marriage to the breadwinner-seeking Rula (an underused Karen Black) and the professional dead end in which he’s found himself. Unable to find steady work, the ostensibly once successful-enough Ed has gotten hooked into a pyramid scheme helmed by a self-help-cum-real-esate guru (Michael Greene). The latter’s whole thing seems to consist of nothing more than charging people $3,000 to attend seminars whose driving motivational speeches consist only of typical failure-paves-the-way-for-success platitudes. Ed is tasked with finding people on the street who’ll agree to listen to all the bloviation. (He must be the least effective of all the people in his same shoes: All the events that we see have nearly all their conference chairs filled, but we see Ed almost exclusively struggling to attract interest.)

Ed meets Rubin only because the latter, a young recluse, has been forced by his mother (Anna Louise Daniels) to leave their shared apartment, in which he doesn’t seem to do much besides crank up his music and play with a mouse-shaped squeak toy with a dedication even a dog couldn’t keep up with. We imagine that she says the kind of thing she does near the start of the film to coax him to leave his cocoon of a bedroom all the time: that he won’t get any dinner or be able to use his stereo unless he’s shown her evidence that he’s tried to go out and make a friend.

Rubin’s serendipitous happening upon Ed will count, to his eye, for something to his nagging mom. He invites him back to their place under the guise of going to the seminar. That will turn into — and I won’t go into the details — Ed reluctantly accompanying Rubin on a long drive into the middle of the Utah desert. Rubin’s beloved pet cat recently died, and he’s been keeping it in the freezer since. He thinks somewhere in the area’s vast sands will speak to him as a perfect burial site, which he claims to have not yet been able to find.

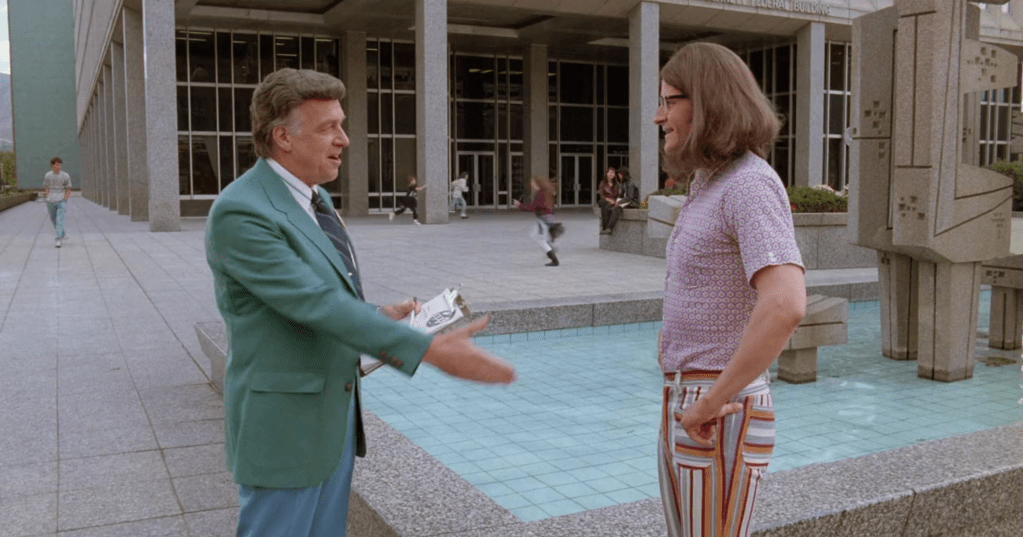

Howard Hesseman and Crispin Glover in Rubin & Ed.

Ed is more than likely right when he infers that Rubin is so hesitant to bury the cat because once he does, he won’t have anything else. (The callous observation will probably inspire the strongest emotional reaction you’ll have related to anything involving Glover’s goofy character.) The car will, not surprisingly, eventually break down in an inopportune place. Though Harris pads things out with some quirky comedy that comes close to not working — mirage-gripped Rubin imagining that he’s floating on an inner tube in a lake through which his suddenly alive and anthropomorphic cat is water skiing; stumbling upon a trailer spray-painted with never-explained anti-Andy Warhol sentiments — it’s not so much the movie’s comedy that makes it worthwhile, or even the fractious kinship that surfaces between its title characters. It’s how persuasively Hesseman locates his pitiable but no less relatable character’s despondency. (Tellingly, the suit he wears has a big yellow button on it that says “WHO AM I?,” which communicates something different to the viewer than to the passersby he’s trying to entice.)

Ed tries to smile through everything with car-salesman fakeness for a good chunk of the movie before realizing his denial is no doubt only making things worse. He wouldn’t like to think of himself as that similar to Rubin, but he can only for so long stave off the truth that they’re both resolutely alone and far from anything like professional and personal satisfaction. Some of that is rooted in the world’s cruelties. But perhaps more comes from their analogous inability to admit how their false conceptions of themselves are stymying anything like growth. Rubin & Ed could be longer than its slight 82 minutes; I wanted to see more of these men’s lives outside each other. But no matter how much outlandish comedy it’s wrapped in, its central affliction packs an unexpected amount of punch.