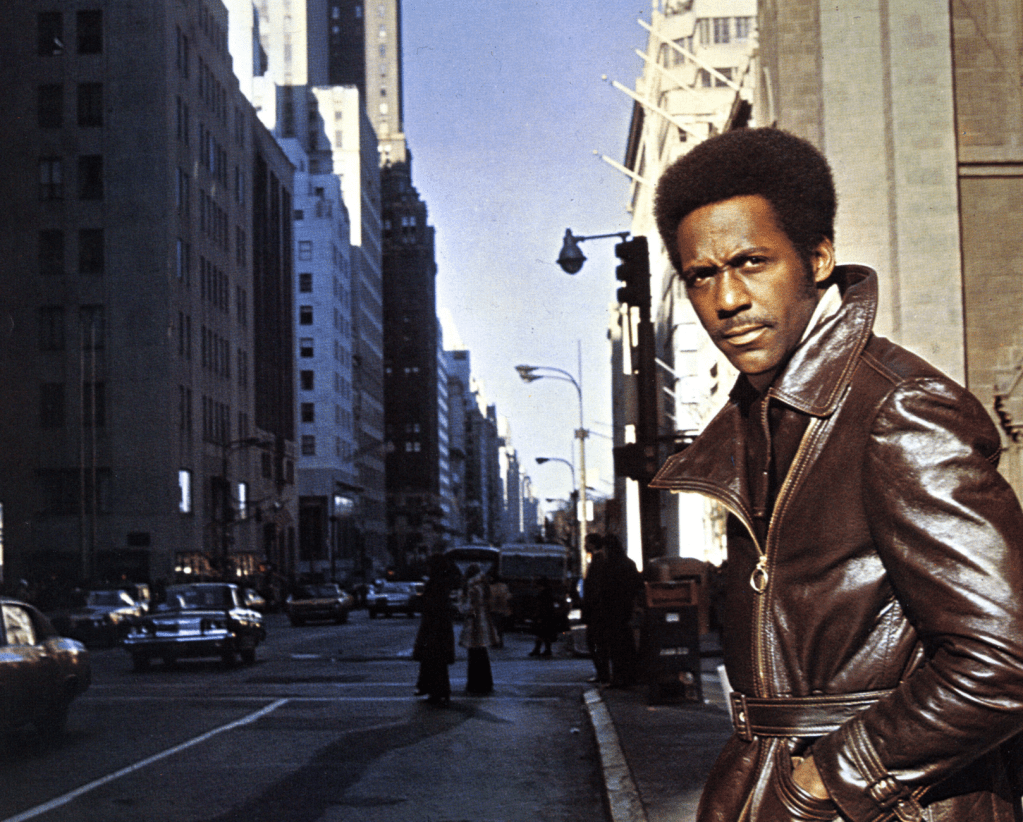

Isaac Hayes gives Richard Roundtree a lot to live up to. Before we’ve even heard private detective John Shaft hold a conversation in the 1971 crime thriller named after him, the soul-music great’s strutting soundtrack lyrically explains the kind of man the main character is. As the Roundtree-portrayed Shaft strides through the New York City streets, stylishly dressed in a color-complementary dark brown leather jacket and pants, Hayes asks a litany of questions we know the answer to as the opening credits roll. “Who’s the Black private dick that’s a sex machine to all the chicks?” “Who is the man that would risk his neck for his brother man?” “Who’s the cat that won’t cop out when there’s danger all about?” Because it musically sounds better that way, the point is harped on by a chorus of women that together confirms each question with an enthusiastic exclamation: Shaft!

In his breakthrough performance, Roundtree, who by Shaft’s January 1971 production start had mostly worked in commercials, doesn’t have to overexert himself to convince us he’s all the things Hayes says he is. Like his movie-PI predecessors — Humphrey Bogart (1941’s The Maltese Falcon, 1946’s The Big Sleep), Dick Powell (1944’s Murder, My Sweet), and William Powell (the Thin Man series of the 1930s and ’40s) among them — his Shaft is immovably unflappable. He never walks into a room without appearing to be the smartest and hardest-to-intimidate person in it.

Roundtree’s smooth, I-am-who-I-am confidence conceals the more-than-probable misery with which a lone-wolf private eye lives. It also, because it seems like Roundtree has been doing this kind of thing for a long time, draws attention away from how significant the character is. Today his Shaft is commonly recognized as the first Black action hero and for groundbreakingly imbuing Black male representation in movies a sexiness that had largely been missing in the studio-sanctioned, white comfort-pandering films of the preceding decade. (Shaft also continues the work of 1967’s In the Heat of the Night and 1970’s Cotton Comes to Harlem, whose Black leads were bold, sharp-witted detectives — a profession that had for decades been exclusively filled in by white actors in mainstream movies.)

Richard Roundtree in Shaft.

It almost wasn’t that way. Shaft’s lead had been envisioned as white by its studio backers before its director, photojournalist-turned-filmmaker Gordon Parks, shrewdly intervened, too propelled by a desire to make a movie in which audiences would “see the Black guy winning” to passively stand by. (Shaft is, it’s worth mentioning, Black in the homonymous 1970 Ernest Tidyman book from which the film is adapted.)

The force of Roundtree — whose Shaft switches physique-flattering turtlenecks as readily as he does docile, interchangeable bedmates and who charges toward danger like it were no different than somewhere safe — is enough to carry Shaft. Without him and the moody lensing of Harlem (particularly at night) by cinematographer Urs Furrer, the movie would be more weighed down by its rather mechanical narrative. Short on the sinuousness expected of detective movies, it sees Shaft working to avoid getting derailed by a ready-to-revoke-his-license police department while trying to rescue the daughter (Sherri Brewer) of a crime boss (Moses Gunn).

Richard Roundtree in Shaft.

Shaft resents the latter for luring ordinary people into lives of crime and for pushing drugs into the community. He rationalizes his involvement because the kidnapping is the result of a bubbling war between the kingpin and the mafia — and any residual messes would only jeopardize the public safety he wants to protect — and because he gets $50 a day, plus expenses, and an agreement from his intimidating client not to breathe down his neck as he looks for answers.

Though the investigation is mostly rote, it’s not devoid of any spark. One inspired scene finds Shaft posing as an ingratiating bartender to ensure the arrest of some mafiosos grabbing drinks at the bar he’s temporarily adopted. And the film’s climactic rescue sequence is so well-choreographed that when Shaft bursts in through a window, weapon in hand, to save the girl he’s been after all movie long, I had to choke down a cheer.

Neither of the über-successful Shaft’s two sequels, which came out annually after the first movie’s wide July 1971 release, was as successful as the original. But the film still did plenty to pave the way for other characters in its protagonist’s Black-action-hero mold. There were, more immediately in the Blaxploitation genre Shaft helped launch, movies like 1972’s Super Fly and a quadrant of Pam Grier-headlining vehicles (1973’s Coffy, 1974’s Foxy Brown, and 1975’s Sheba, Baby and Friday Foster), and, further down the road, several action-oriented features starring the likes of Denzel Washington, Wesley Snipes, and Will Smith. Shaft functions superbly as a coming-out party for Roundtree’s screen presence and as a beacon of possibility that would continue to be chased after.