Police Story (1985), the movie director-star-co-writer Jackie Chan touts as his best work, is, indeed, action-filmmaking par excellence. But when it’s not devoting itself to its many limber, Chan-centered set pieces, the high-speed gracefulness of the latter gives way to clumsy storytelling sullied by even-clumsier attempts at comedy.

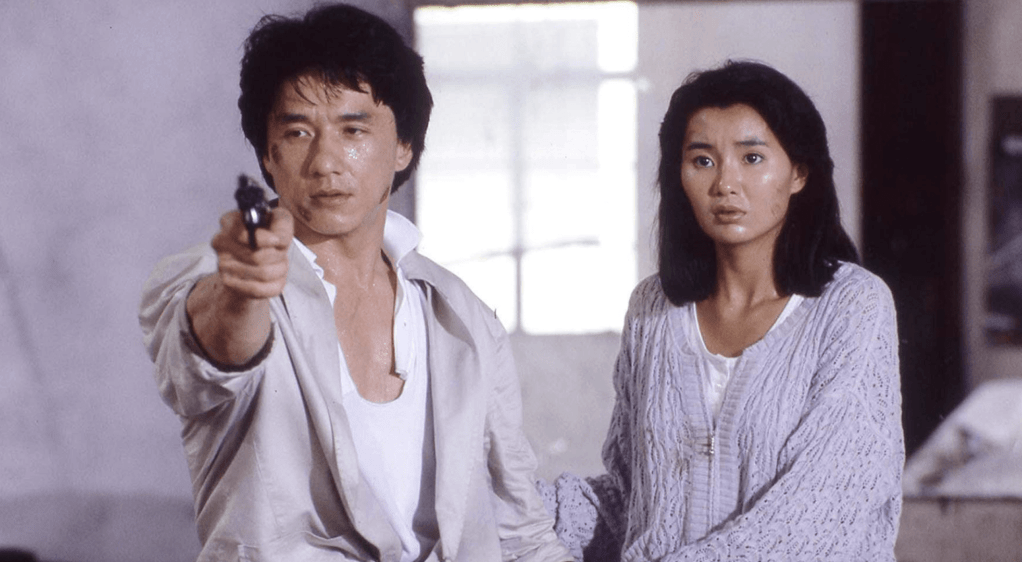

In Police Story — which spawned several sequels — Chan plays an undercover officer, Ka-Kui, who’s been assigned to protect the secretary, Salina (Brigitte Lin), of an all-powerful, seemingly all-seeing drug lord, Chu Tao (Chor Yuen), so that she can testify against him in court. Chu Tao is apprehended by Ka-Kui at the start of the movie after an extended, breathtakingly choreographed multiperson chase through a shantytown. A nauseating quality edges out its thrills: How many of the destitute people living there will be able to get back to a semblance of normalcy after the extensive destruction wrought by Chu Tao and co. and the officers that tail them? (This style of icky demolition-in-the-name-of-action would be echoed, years later, in 2003’s Bad Boys II.)

Poor taste is about as endemic to Police Story as the magnificence of its action, which the freakishly agile Chan spearheads with the nerve of someone unworried about physics and the injuries potentially incurred by surfaces hostile to the human body. The entire arc of Ka-Kui’s girlfriend, May (Maggie Cheung), requires her to either be humiliated by her emotionally cavalier boyfriend or physically harmed, whether being, mid-outdoor argument, thrown off her scooter and onto the concrete by Ka-Kui or, during the film’s otherwise awesomely executed mall-set finale, punted down several flights of stairs by the film’s villains in a move that seems like unspoken punishment for her all-movie-long nagging.

And a slapstick scene in which Ka-Kui, for some reason the only person at his Hong Kong precinct, disastrously juggles multiple emergency calls is rendered DOA on the one hand because police incompetence would be funnier in a movie that wasn’t so ready to ultimately valorize law enforcement, and on the other because many of the calls are being made by women being abused. One has just been raped; another has just been beaten by her husband. Their cries for help are met with Ka-Kui’s total lack of concern. (His ungainliness is capped off with him, relieved to be getting off the phones instead of following up on what he’s just heard, blithely downing a bowl of ramen with the assistance of pencils-as-chopsticks.)

Police Story’s comedy bespeaks the difficulty of inserting the genre into police-related matters. If it’s not satirical enough, then it might inadvertently suggest that professional ineptitude is excusable as long as an assigned job is eventually done. The movie doesn’t indicate that its comedy is meant to be implicitly critical; it seems to, instead, want to show that policing can be fun, and that you can be a goofy everyman like Ka-Kui and not only get results but have the potential for dauntless, on-the-ground superheroism. The action sequences function first as awe-inspiring showcases for Chan’s once-in-a-generation nimbleness, second as temporary relief for the queasiness arising from nearly everything else.