The thought one is likely to have most frequently while watching Harry Kümel’s Daughters of Darkness (1971) might sound something like this: Delphine Seyrig is gorgeous. The observation persists throughout all her movies — even in the film, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), for which she is arguably most celebrated and for which she’s dramatically deglamorized as a worn-down housewife nearing a breaking point — but Daughters of Darkness visually venerates her beauty to the point of it being overwhelming.

That’s another way of saying that the movie successfully achieves one of its main aims. In it, the high-cheekboned actress plays a vampire — ostensibly Elizabeth Báthory, the infamous 17th-century noblewoman long-rumored to have bathed in the blood of freshly killed virgins to stay forever young — whom we’re supposed to believe has no problem parlaying her porcelain-like good looks to seduce and destroy. (Her marble-white visage generously rouged in a way that implies her blood-parched character is incapable of naturally generating a flushed face, platinum-blonde Seyrig is styled to resemble Marlene Dietrich.)

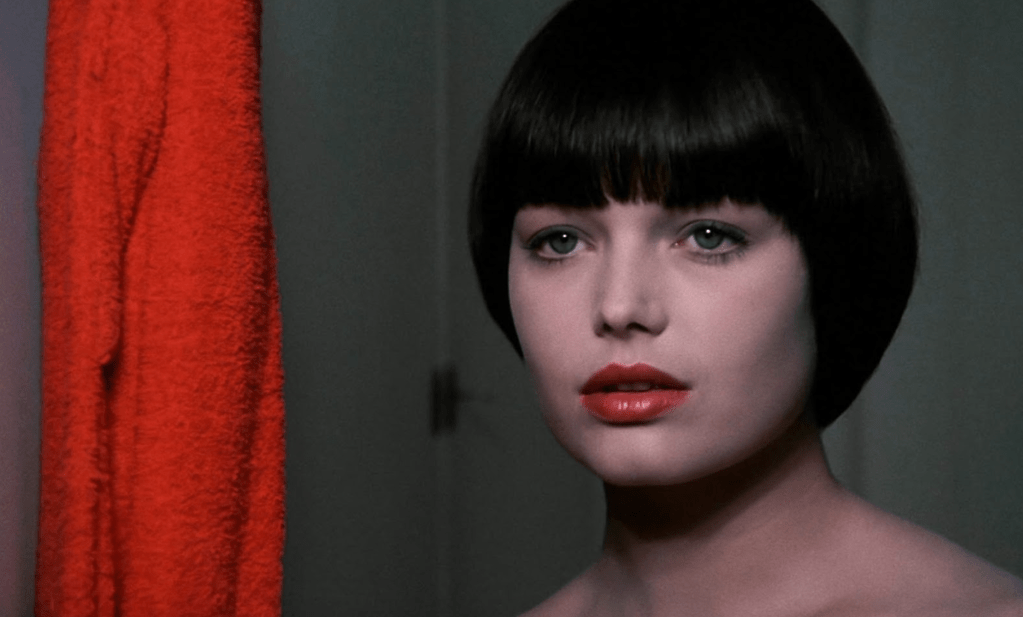

Andrea Rau in Daughters of Darkness.

In the contemporarily set Daughters of Darkness, Seyrig looks both young and plausibly hundreds of years old. She speaks exclusively in an unsettlingly calm whisper, a little flirtatiously and a little like she was comforting a to-be-euthanized pet in a vet’s waiting room. Her gleaming, red-lipsticked mouth is almost always curved up into a pleasant — but conspicuously scheming — smile. That the colors of her elegant array of costumes are intentionally Nazi flag-colored — black, white, and red — as much add to the malice she exudes as give the threat she poses a metaphorical frisson. Fascism can be alluring to the vulnerable; it’s not hard, if you’re not careful, to submit to its delusionally, destructively self-first interests. Lord knows that Elizabeth is herself destructively selfish, but we can tell that she’s so many times gotten what she’s wanted, in a potentially bloodthirsty sense, that it wouldn’t be accurate to call her delusional.

Daughters of Darkness is still chillily efficient at being what it is on the surface: a horror movie where there doesn’t seem to be a way for its main character, the fawn-eyed Valerie (Danielle Ouimet), to wrest control from someone who has power over her. There’s Stefan (John Karlen), the rodent-like man she just married with deep-in-his-bones mommy issues who becomes exponentially more dominating and abuse-prone during the literal honeymoon period in which the movie takes place. (Daughters of Darkness begins with them on a train, snugly in bed post-rushed elopement; the rest of the film unfolds in the imposing, sinisterly empty grand hotel on the Ostend waterfront they’re staying at in the just-wed aftermath.) And there is Elizabeth, trailed everywhere by an openly miserable, full-lipped companion (Andrea Rau), who’s also taking up residence at the arch- and column-heavy lodge. She seems not merely to want to embed herself with the newlyweds, but with Valerie specifically. The past-middle-age concierge is terrified at the initial sight of Elizabeth: he knows that she visited some 40 years ago, when he was still a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed bell boy, and her aristocratic good looks — nor her 1930s leading-lady sense of style — haven’t at all changed in the time since.

Valerie turns out to be equipped to leave Stefan, who makes it escalatingly obvious that it’s not love he’s after but a woman over whom he can have dominion that isn’t his much-fretted-over mother. (He has an easier time hastening into marriage than saying “I love you”; his sadistic streak is portended by his getting apparently turned on as violent crimes, perhaps committed by Báthory, are luridly described.) Valerie doesn’t fall into the trope of an abused woman who can’t bring herself to detach herself from her husband. She falls into something maybe scarier: becoming the object of affection of someone who might not be quite of this world, who has the uncanny ability to appear, in a split second, when you think you’ve gotten her off your trail. (Four murders have taken place around town in the same last few days — all of whose victims had deep, fang-like punctures in their necks — that Elizabeth has been around.)

Delphine Seyrig in Daughters of Darkness.

Daughters of Darkness isn’t off the hook for perpetuating a stereotype that was common at the time in lesbian fiction: of a same-sex-attracted woman being a predator, looming over a naïve, usually straight victim just past girlhood with motives that go beyond earnest attraction. But at least it doesn’t have the same leering style of many of its decade’s similarly premised movies, particularly those helmed by Jesús Franco and Jean Rollin. Those men’s proficiency at cultivating eerie, erotic phantasmagoria didn’t preclude a regularly objectifying gaze, leching over women’s bodies with almost salivating interest. Kümel is more concerned with developing a malevolent but seductive atmosphere: plum-purple night skies zapped with lightning; fog-slick streets devoid of much life; moonlit ocean shores; shards of star-shaped light beaming off glossy, blood-red fingernails.

Daughters of Darkness isn’t very action-packed. Complaints that it doesn’t offer much beyond its style and Seyrig’s moth-to-the-flame performance are not ungenerous. (Its potency would certainly double if Valerie were afforded more interiority; she’s mostly a deer in headlights played by a rather inept actress.) But there’s power in its mostly muted style of horror. Omitting the violent outbursts that tear through its last act, it’s the kind of genre exercise that confidently embodies a seldom-valued approach in horror: spending so much time creeping up on the viewer that, by the time its seemingly imminent nightmare has finally arrived, you feel like the floor has vanished beneath you, your feet, not your eyes, the first to notice.