It’s said that Macbeth is cursed. The superstition holds that if during a production of the Shakespeare drama someone dares to utter the actual title and not the sidestepping “Scottish play” nickname, then bad luck will befall those involved. No one in Dario Argento’s Opera (1987), which orbits around an adaptation of Verdi’s musicalization of the 1606 tragedy, seems at all concerned with the play’s reputation. Such could be part of why things will devolve enough to make the movie’s iteration of the play seem like a contender for a “most cursed” badge.

The things that happen in Opera make it a marvel that its focused-on version of Macbeth is never canceled or even postponed. But, then again, this is a horror movie that features some of the most baffling decision-making ever in a genre notorious for featuring characters who are baffling decision-makers. (Terrible things must keep happening, after all, to fill out at least 80 minutes rather than see a movie prematurely end because a character wisely decides to skip town and lay low until the coast is clear.)

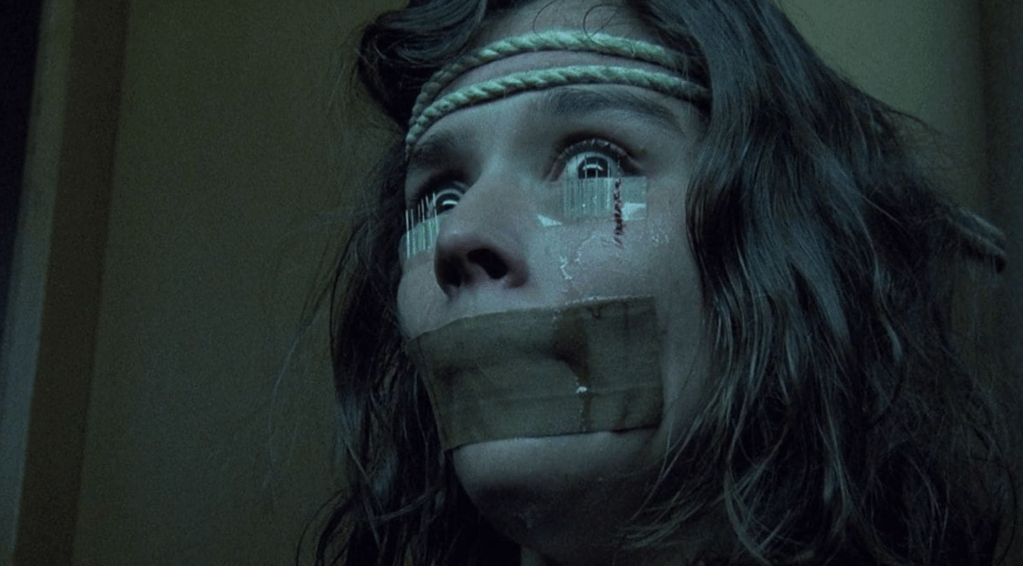

Here’s what happens in Opera: an on-the-come-up opera star, Betty (Cristina Marsillach), at the last second replaces the acid-tongued prima donna who was set to headline a high-profile production of Macbeth. Then Betty is terrorized by a black-masked man who gruesomely and systematically kills several people she’s close to when he’s not clandestinely watching her through her apartment’s absurdly roomy vents. The murderer — maybe or maybe not a maniac of the superfan variety — makes things more torturous for Betty by always striking when she’s with his latest victim of choice. He’ll wait until she’s alone in a room and incapacitate her so that he can tie her up. Then he tapes little needles beneath her eyelids — a nasty move Argento has jokingly professed to wanting to himself perform on more squeamish audience members — so that she’ll be forced to helplessly watch the person she’d just been with be horribly maimed. She’s only cut loose when the work is done.

From Opera.

One would think the first murder that takes place would be enough for Macbeth to be at least temporarily paused. But Betty is unnaturally blasé about it — she doesn’t call the police, and listens to calming affirmations in bed to self-soothe — and continues on with the commensurately violence-downplaying production. Putting on a professional brave face is among the few things she does in Opera that makes some sense. Is it that unrealistic for an artistically hungry dreamer not to want to fumble what seems destined to be a big break?

But once the killings in Opera become too much for Betty and the people around her to keep feasibly ignoring, the credulity-stretching starts to get laughable. Why would Betty, her eyes bleary from eye drops, open her apartment door for a lone police officer she cannot see when she is definitely being hunted by a serial killer who would almost certainly not be opposed to posing as someone trustworthy to get into her good graces? And how could a fleet of ravens — used as props of sorts during Macbeth’s production and continuing Argento’s long-running proclivity for featuring animals in his movies — identify one man out of thousands in a crowd as the killer because they’re collectively mad at him for attacking some of their own earlier in the movie?

Argento had already forged a casual relationship with sound reasoning in his previous movies. No one could say with a straight face that his 1977 magnum opus, Suspiria, or his twisted coming-of-age story Phenomena (1985) make total sense. Things after Opera, a new nadir, would not subsequently pick up for a director noticeably on the decline.

William McNamara in Opera.

Argento’s way with the camera counteracts much of what can make Opera frustrating. If it shows a thorough logical lapse in his wobbly-as-is storytelling, it, on the flip side, makes the case for the director at his most stylistically confident. It’s full of nifty tricks that make the film, if not thrilling in its narrative, thrilling to watch. Much of its opening scene plays out in the reflection of a bird’s frenetically blinking eye. We see poison being poured down a drain as the drain, if it had the ability to, would see it. Later, we watch a bullet, in slow motion, torpedo through a peephole, speeding toward the skull of the doomed woman looking through it.

Opera’s cameras are already restless, scanning surfaces and people as if they were looking for something they’re not supposed to. But nothing compares to the rush of seeing through the killer’s POV as he darts around the opera house, charging up flights of red-carpeted stairs or barreling down into the building’s dust- and cobweb-covered basement floor on the hunt for something unknown. (You forgive Argento for, during those latter moments, often placing the camera low enough that the implication is that the murderer is somewhere around 3 feet tall.)

Opera conspicuously wanting to tell a shocking, twisty story prevents one from excusing its incoherence the way one could with Suspiria: that this is just nightmare logic at work, and that there isn’t much need to think too deeply about what has gone on when everything looks this good and feels this singularly bad. Like Suspiria, though, Opera looks very good. Argento’s formal assuredness halts outright embarrassment.