Knowing now that John Huston’s final feature, The Dead (1987), was released about three months after his death makes the movie initially feel, a little, like an emblematic farewell gathering for the legendary director. The James Joyce adaptation, scribed for the screen by Huston’s son Tony, almost entirely uncoils during an Epiphany dinner in early 20th-century Dublin. Made cozier by the gentle dusting of snow outside, the gathering is being put on by a pair of middle-aged, unmarried sisters, Kate and Julia (Helena Carroll and Cathleen Delany), and their supremely gifted pianist niece, Mary Jane (Ingrid Craigie).

Few people there appear especially close outside the annual festivities. The warm glow of the siblings’ townhouse seems to have as much to do with its literal sources — the smattering of lamps studding each decorously appointed room — as the guests’ affection for their hosts. The Dead’s majority-Irish cast is convincingly cordial in the way one expects from settings like it, where most of the talk is small and friendly and any suggestions of conflict never too worryingly swell. But there’s a practically tactile melancholy in the room that one of the guests, Kate’s professor nephew Gabriel (Donal McCann), explicitly points out during his toast. Even if many of the attendees exclusively see each other when they’re summoned by Kate and Julia, it’s hard not to feel wistful for those who weren’t able to make it this year, whether because of a conflict or, more heartbreakingly, the limits of their mortality.

Kate and Julia get teary as Gabriel ends his speech on a positive note — he praises their generosity and the intimate beauty of the tradition they’ve cultivated — that would be stirring regardless of if The Dead were Huston’s final film. But that it was, and that the heart disease- and emphysema-afflicted filmmaker powered through his fast-diminishing health to finish it (he was wheelchair-bound and oxygen tube-fastened as he conducted his actors), makes Gabriel’s allusions to time’s inflexible passage and the losses that come with it almost overwhelmingly emotional.

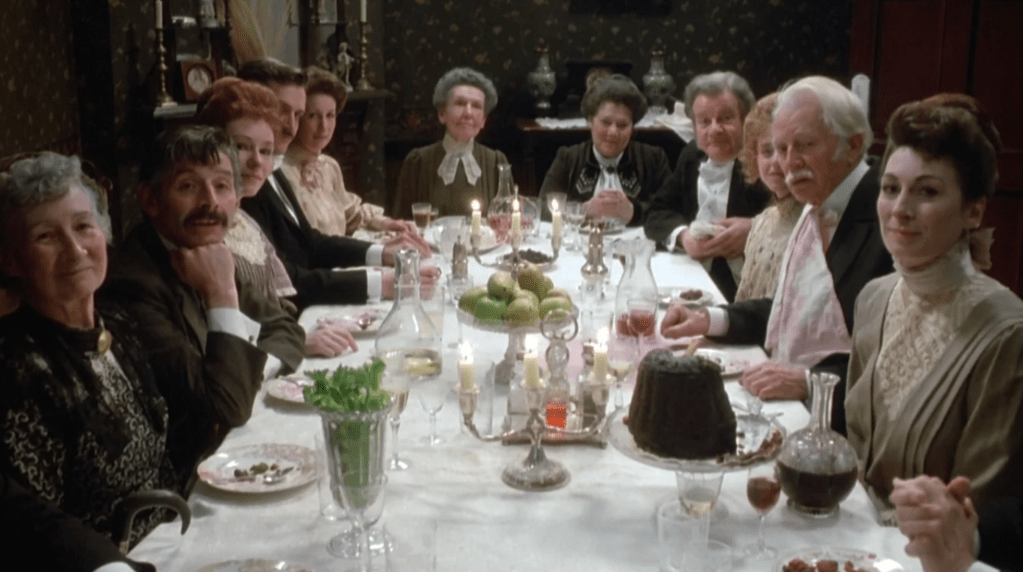

From The Dead.

The film’s involvement of both Tony, who lent his father a directorial helping hand in addition to his screenwriting duties, and Huston’s third child, Anjelica, doubles it. The latter was so sorrowful watching her dad decay that in 2019 she concluded to the Los Angeles Times that a subsequent Epstein-Barr diagnosis was probably an extension of her deep anguish. “I think it had to do with the burden of watching him struggle on a day-to-day basis and being part of this struggle,” she said. “But he never gave up. I think his work became a savior to him.”

Anjelica’s character, Gretta, is married to Gabriel. She grounds The Dead’s home stretch, which crushingly delivers a different form of gloom than the earlier part of the film. The welcomely time-consuming dinner is more celebratory and appreciatively misty-eyed than glum. What the night’s whiffs of mournfulness ultimately activate in Gretta — memories of love with a dark-eyed boy prematurely lost when she was a teenager, to which her current marriage clearly cannot live up — makes the film end with a certain defeatedness.

As shattering as it is, it feels in keeping with the ethos Huston cultivated across the close to 40 movies he helmed in his lifetime. Though not entirely hostile to happy endings, Huston didn’t bend toward easy sentimentality. (He did, though, have an enduring soft spot for The Dead’s central Ireland: He lived in Galway, and there raised Tony and Anjelica, for about two decades.) It feels right for the clear-eyed filmmaker to have made a death-pondering movie, while himself aware of his imminent end, that lets the regret, the what-could-have-beens, linger.