Kate Davis’ 2001 documentary Southern Comfort catalogs what could be seen as a murder in slow motion. Davis’ subject, whom she met at a conference, is Robert Eads, a transgender man from rural Georgia who in 1996 was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. After a period of having doctors brush off his mounting health concerns — he was waking up in pools of blood — Eads saw his eventual, and likely treatable, prognosis met with a nauseating lack of concern. More than 20 practices refused care because they didn’t want to “embarrass” themselves in front of patients. Once Eads finally found some help, it was too late. He died from the disease in January 1999, about a month after his 53rd birthday. “It’s kind of a cruel joke,” Eads says early in the film, which covers the final four seasons of his life. “That last part of me that is really female is killing me.”

I concur with the writer Sally Jane Black that Southern Comfort doesn’t quite feel sufficiently angry enough on Eads’ behalf. It would feel more just to righteously name the places and people who one credibly could say homicidally denied Eads the care that could have saved him or at least have prolonged his life. But because there would more than likely be a legal morass to be time-consumingly wade through if that approach was employed, Davis instead tries to do justice to who Eads was.

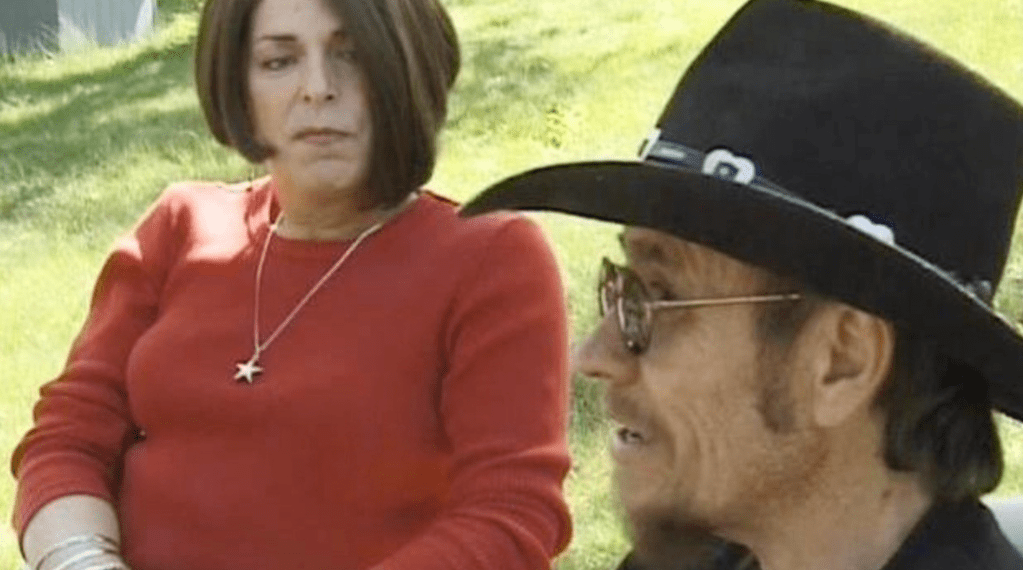

Stephanie and Cas Piotrowski in Southern Comfort.

Much of that understanding comes from Southern Comfort’s emphasis on his loved ones, especially the chosen family of fellow transgender people on whom he had a profound impact: his lover, Lola, whose meant-to-be-casual relationship with Eads becomes meaningful enough for him to, as he puts it, “hold on for her”; two younger men, Max and Cas, who are alternately characterized as “sons” and people Eads, given their comparably timed gender transitions, “grew up with”; and his briefly seen adult cisgender son, who recently made Eads a supremely happy grandfather. Though not trying very hard to retire the “mom” appellation or use correct pronouns, the latter means it when he says Eads would have been the best man at his wedding had he lived long enough to attend the hypothetical ceremony.

Eads transitioned in his 40s. In one memorable if constructed-feeling scene in which he looks back at old pictures of his pre-transition “evil twin sister,” he cheekily describes his childhood and early adult life as his cross-dressing years. He’ll later recount the paradoxical feelings pregnancy inspired — it was objectively amazing to grow another person but overwhelmingly uncomfortable with his then-private understanding of his gender — and how living as a lesbian after his marriage, though hewing closer to his conception of himself, still didn’t feel right. Eads’ family, though not outrightly giving him an undefrostable cold shoulder, has never fully accepted him. Few people in his conservative-leaning town, though, know that he isn’t cis. In an unsettling introductory scene, he brings up a polite conversation he recently had with a local who invited him to a meeting of an organization known to be an offshoot of the KKK. Eads couldn’t help but wonder, in the moment, how it would play out if he introduced himself to the group’s members with full transparency. (Davis has said in interviews that Eads expressed fears to her of waking up with burning crosses on his front lawn.)

You immediately feel, as Davis has said she herself did as she shot the film, deep affection for the eloquent, sensitive, and wryly funny Eads. He’s the sort of person people evidently love to have around so much that imagining the hole he’ll leave behind feels unfathomable, even as he’s being wheeled into hospice. There he’ll insolently declare, with his trademark mischief-brightened smile, that the pipe he smokes must be a sort of protectant: His cancer has spread everywhere but his lungs.

Lola Cola and Robert Eads in Southern Comfort.

Davis’ intimate — and financially practical — home video-like shooting style makes you feel like you’re in the room with her. Though it doesn’t take its attention off its core set of subjects, Southern Comfort still makes you think about how many others have faced or are facing something similar to Eads: denied medical help or intervention because they don’t ascribe to their assigned gender. Davis’ gaze as a cis person, and also as a filmmaker with an obligation to edit together a narrative from hours of footage, additionally saturates the film with an interesting tension — the inescapable fact that Eads, by being presented by an outsider with more societal power, is concurrently being “remembered and misremembered at the same time,” Asa Mendelsohn wrote a few years ago.

Aside from some of its framing and the limitations inherent in documentary filmmaking, Southern Comfort does not particularly feel, as one might wish it would, like a relic. Even if the general public has become more aware, in the last 25 years, of the medical discrimination that contorts trans lives, the strain of injustice that underpins its central tragedy dismayingly continues to persist. Southern Comfort underlines the needless cruelty without letting victimhood ultimately confine memories of the extraordinary person that Eads was.