Waiting to Exhale (1995) celebrates an often taken-for-granted truth that’s rarely a movie’s driving force: Amid life’s ceaseless churn of disappointments, one of few things you can count on is friendship. In the film’s milieu, which is seen through the eyes of four Black women, men are almost always good for nothing but emotional chaos. And the victories of one’s professional life, if working in a conventional workplace, are dependably sullied by sexist barriers — cyclical demands to prove oneself in a way male colleagues are almost certainly not.

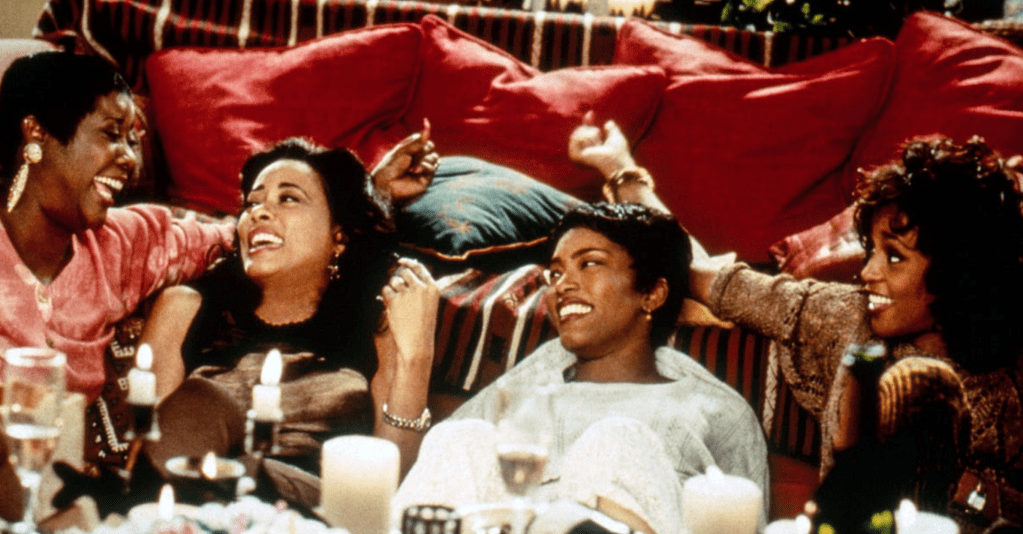

Marking the directorial debut of actor turned filmmaker Forest Whitaker, Waiting to Exhale is a little narratively ungainly; its braided storyline, constructed by screenwriters Ronald Bass and novelist Terry McMillian, moves back and forth between its lead characters’ dramas with episodic, slightly awkward “it’s her turn now” obligation. But it’s easy to love for the brutal-but-invigorating honesty with which it treats dating and relationships, the tight-knit friend-group rapport between its quartet of well-cast actresses (Angela Bassett, Whitney Houston, Loretta Devine, and Lela Rochon), the smoothness of its excellent Babyface-steered soundtrack, and its skillfulness with kiss-off-style moments. One is instantaneously recognizable regardless of if you’ve seen the film: the sight of Bassett apoplectically setting aflame, with a match she’s just lit a cigarette with, her philandering husband’s prized convertible, which she’s vengefully stuffed with his clothes and other sentimental ephemera. The other — of Houston telling off and then dumping water into the lap of a family man who cockily presumes she’ll interminably wait around for him to upend his life for her — becomes unforgettable the second her drink escapes its glass.

Waiting to Exhale’s leads are all in transitional phases of their lives. Houston’s character, Savannah, has a habit of switching cities when she decides that there are no good romantic prospects there — a custom that leads her to relocate from Denver to Phoenix, where the film is set, at the movie’s start. She has a flair for getting pulled into the orbits of emotionally and/or maritally unavailable men, and has agreed to a pay cut at her TV-station job to prove her producing chops on a trial basis. Bernadine (Bassett) has spent the last 11 years as a housewife, filing away a hard-earned, now-dust-collecting MBA and deferring dreams of opening a catering business for a husband (Michael Beach) who coldly informs her near the beginning of the film that he’s leaving her. The announcement leaves her thoroughly rattled, practically nauseous over all the years frittered away on domestic self-sacrifice.

Angela Bassett in Waiting to Exhale.

Robin (Rochon) is successful at work but in her personal life trying but failing to move on from an emotionally immature married man (Leon Robinson) who habitually makes false promises of a future to her. (Her attempts to romantically branch out — all with guys she hopes will not be losers but turn out to be — are responsible for some of the film’s most bruisingly funny flourishes.) And single mother Glo (Devine), whose subplot is the most afterthought-like of the bunch, is anxious about an approaching empty nest: her 18-year-old son (Donald Faison) is soon leaving for a career opportunity in Spain.

The fact that nearly every man these women get involved with is wed — even a tragically backstoried potential rebound for Bernadine — is a little comical. Are pickings really that slim in Phoenix? But that also feels beside the point. A shared trait among Waiting to Exhale’s collection of both two-timing and definitely single would-be paramours is that the majority of straight men are almost genetically predisposed to be disappointing. Their relationship status can’t change what’s innate. Mainstream movies tend to believe in love as a solution for all of one’s problems. Waiting to Exhale, ever pragmatic, isn’t so sure.

I love how that pessimism never fully subsides. Waiting to Exhale’s happy ending notably doesn’t match each of its characters up with their dream man at the last minute (though one of them seems to have found a keeper in her neighbor) as a salve for everything. Instead, everyone arrives at a new level of self-acceptance, learning to appreciate what they have and coming to see marriage as a plus rather than something on which the success of one’s life hinges. It’s a contented goodbye-to-all-that destination the movie finds just as worthily aspirational as the love-fetishizing fairy-tale-esque ones these women once prized. Some things about Waiting to Exhale, which just turned 30, haven’t aged well: flashes of anti-gay slang for comedic purposes; indulgence in fatphobia as shorthand for why a certain main isn’t worth pursuing. (He’ll provide other reasons, but still.) But the movie’s appreciation of friendship and calls for self-respect haven’t.