Based on Nora Ephron’s autobiographically tinged novel from 1983, Heartburn (1986) is a curious case. It’s a funny, likable movie that you come to also resent, a little, for never quite going far enough. (It doesn’t help, either, that director Mike Nichols’ more widely revered movies about relationships on the rocks, 1966’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and 1971’s Carnal Knowledge chief among them, are comparatively so forceful that you wonder if they, perhaps, are going too far.)

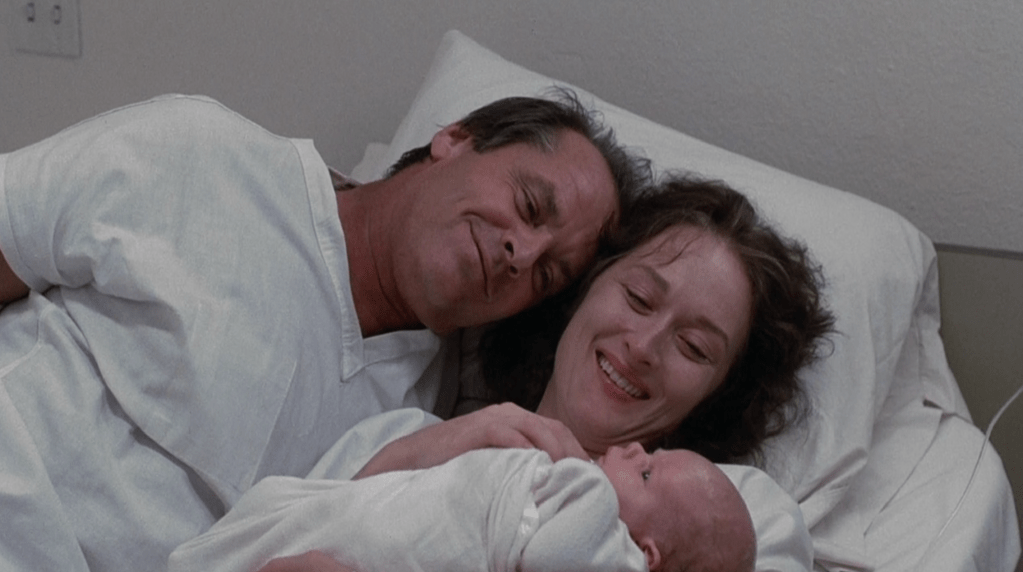

The divorce movie, for which Ephron also wrote the screenplay, is inspired by its author’s own experience, in the late ’70s, marrying against her better judgment (and then splitting up from) the womanizing-prone investigative journalist Carl Bernstein. A dark-haired Meryl Streep plays the Ephron stand-in, a Manhattan-based food writer named Rachel. Jack Nicholson is Bernstein counterpart Mark, who’s not a reporter but an esteemed political columnist from Washington, D.C. Despite the name changes and other narrative adjustments, the storyline generally matches Ephron’s own. The short-lived marriage results in two children; because paper-trail evidence of adultery is discovered near the second pregnancy (“You can’t even pay cash like a normal philanderer?” Rachel fumes), the understandably big emotional response results in an earlier-than-expected delivery.

You like Streep’s Rachel immediately. Then again, given Ephron’s own well- (and self-) documented charm, it would be impossible not to. She’s witty; simultaneously self-aware and affably neurotic; and predisposed to half-jokingly fretting, for instance, that she can’t move to Washington because the bagels there aren’t nearly as good as New York City’s. Mark is, in comparison, pretty rarely seen and one-dimensionally villainous. Save for a delightful moment where he breaks out into song during a pizza dinner on the couch in the falling-apart townhouse he and Rachel move into at the film’s start (a neat architectural metaphor for their marriage’s unstable foundation), you can only react to him by both simmering and also feeling like you don’t particularly know him.

You feel like you’re only getting a sketch of Rachel and Mark as a couple. Quickly made conclusions — that these two union-skeptical people should’ve listened to their initial instincts, that Rachel considering running away from the altar might have actually been the universe trying to intervene for her own good — overpower their marriage’s day-to-day contours. Almost everything in Heartburn is emotionally counteracted by a feeling of inevitability. Rachel’s victimhood maddeningly supplants nearly everything else about her personhood, too, though one could soundly argue that that’s part of the point: a paranoia-inducing relationship can do that to a person.

Ephron’s long-proven finesse with amusing specificity saves Heartburn from feeling too much like a softball, paint-by-numbers divorce movie. A group-therapy session would get randomly interrupted by a petty criminal (a multidimensionally unwelcome Kevin Spacey) demanding that its members — one of whom (Joanna Gleason) hilariously bleats about how much more action-packed Rachel’s life is than hers, even in its misery — hand over all their jewelry in a scene surprisingly played for laughs. Rachel would have the come-to-Jesus moment that Mark is cheating in the middle of a hair appointment, dashing mid-chemical treatment to dig through drawers while looking like a feral madwoman. Rachel would mark the official end of her and Mark’s marriage by cathartically chucking a key lime pie at his face. And though it’s more than probably the result of on-set magic than Ephron’s own scripted guidance, it nonetheless feels in line with her sensibility to have Rachel’s daughter messily shove a popsicle in her mother’s face right as she’s disappointedly finding out that the dozen roses that’ve just been delivered are from a friend she self-preservationally lied to rather than a potentially guilty-feeling Mark. These touches make a difference — but they can only do so much.