Like many high-school seniors, Anthony (Larenz Tate) isn’t sure what exactly he wants to do after he’s handed a diploma. It’s the end of 1968, in the Northeastern part of the Bronx. All he knows for now is that he wants to “do something different.” The fate eventually befalling him in Dead Presidents (1995), the Hughes Brothers’ follow-up to Menace II Society (1993), could definitely be classified as “different,” if, tragically, almost certainly not among the nebulous things he might have had in mind.

Before he gets there, Anthony eventually decides to go with a more conventional next step come June. He’s going to willingly enlist to fight in Vietnam. He wants less to take after his older college-graduate brother and more his father, who often said growing up that he felt like his time as a Marine in Korea helped make him into a man. Anthony stays abroad for the next four years. Later, he’s joined involuntarily by friends from back home, José and Skip (Freddy Rodriguez and Chris Tucker).

When he returns, Anthony feels immediately in freefall. He struggles to find work well-paying enough to support his childhood sweetheart (Rose Jackson) and their young daughter together. He’s so swamped by PTSD that when he goes to sleep — his only real chance to escape this new and unsatisfying life — he’s roundly bombarded with war-tainted images, all gore and dying shrieks and explosions. He starts drinking to lull his demons. His relationships and family life suffer.

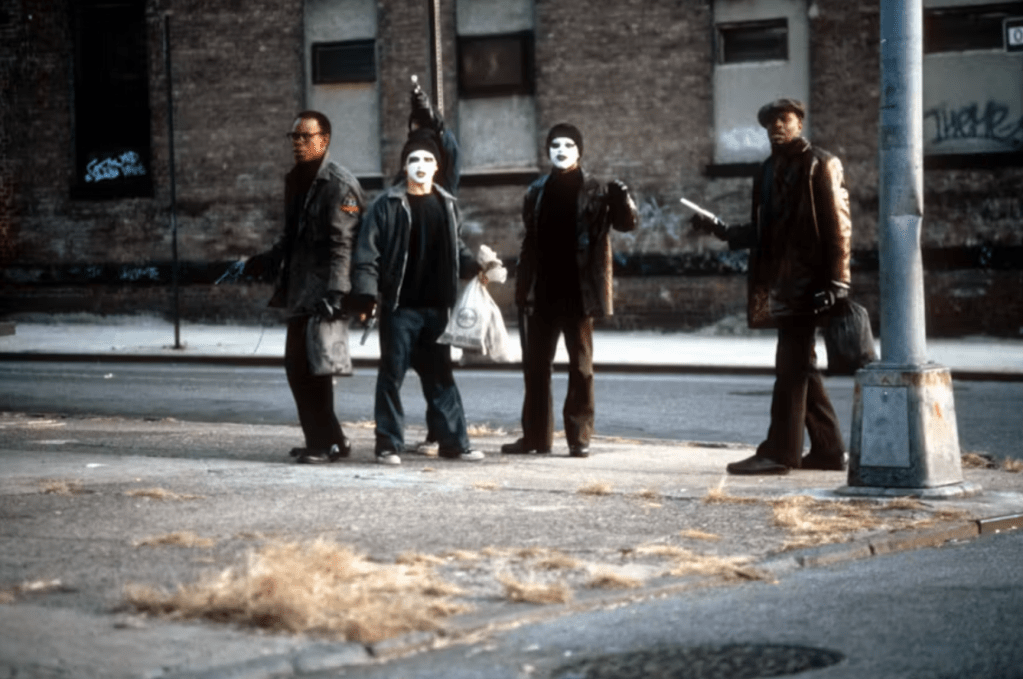

Made when the Hughes siblings were just 22, everything in Dead Presidents works well up to this point, tracking Anthony’s slow breaking apart amid and in the aftermath of war after what is seen, though relatively briefly, as a happy upbringing pocked only by his uncertainty for the future. But the film falters, and never completely recovers, once it reaches the crime-drama pivot for which it’s become known. Before we can fully comprehend what’s going on, Anthony is sitting around a table with some friends, new and old alike, plotting how they’re going to successfully rob the armored car they’ve heard is stopping by the Noble Street Federal Reserve Bank in their neighborhood.

Ensuing is a classically botched heist where just about everything goes wrong before any rights can be enjoyed. Then comes inevitable imprisonment. The closing credits arrive so abruptly that your first instinct is to wonder if a surplus half hour got lopped, the studio interfering after getting nervous about the possibilities of a two-and-a-half-hour-long movie hopscotching freely and confidently between the coming-of-age, war, and crime genres.

None of this is to say that it isn’t fundamentally believable that financial desperation would drive these characters to go this route to solve their problem. It’s more that it feels like a handful of scenes preceding the shift had gone missing. In a movie that makes a point to move at a relatively unhurried, naturalistic place, appreciative when it can be of everyday practicalities and frustrations, a development as extreme as this one — especially when we’ve seen almost none of these characters commit crimes before that might light a fire in them to commit an act so complicated and bold — practically bulges out. It’s like we briefly blacked out and someone fast-forwarded a few minutes under our noses.

The feeling that Dead Presidents is being fast-forwarded through continues for the rest of this movie that otherwise has the kind of strong first and second acts that make you feel like you’re watching a classic criminally robbed of its laurels. It’s still very good. It’s pragmatic and perceptive about the brutal adjustment of post-war life, especially as it relates to the experiences of Black veterans. And the Hughes’ have a discerning way of underscoring minor details that make things feel more lifelike, from the awkwardness of losing one’s virginity to the annoying limitations of living with a fake leg.

Watching Dead Presidents, I thought sometimes of that viral drawing of a horse with a detailed head and stick-figure body. For so much of the movie, the Hughes’ instill in you an assurance that they know what they’re doing and where this story is going. They draw a detailed picture; it’s rare artists so young can create images with their same know-what-they’re-doing certainty. Then they start rushing just when things start to take an interesting new turn. It’s like they got tired of their own movie and wanted to move on to the next thing without giving us a head’s up first.