Like his last foray into the form, 2020’s The Human Voice, Pedro Almodóvar’s new short film, Strange Way of Life, could stand to be a little longer, albeit for a different reason. Based on a 1930 monodrama by Jean Cocteau, The Human Voice is so pleasurable that you wish you could dwell in its claustrophobic and colorful world just a bit longer, even though its pleasure is inextricable from its concision. Strange Way of Life might have had more emotional power if it had more than a half hour in which to pack all its melodramatic detail. Though not totally ineffective, Strange Way of Life’s pithiness has a way of making its central drama, and the interstices of lives lived informing it, come across mostly as a series of poses, a superficial sensation only abetted by the assembly of beautiful Yves Saint Laurent garments it advertises.

That central drama: the 25-years-coming reunion of Jake and Silva (Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal). These cowboys first met as gunslingers, then spent two blissful, hush-hush months together as lovers. Although they can barely suppress the overwhelming joy they feel when seeing each other for the first time after so long, the circumstances bringing their estrangement to an end are not happy. Jake, now a sheriff, is looking for the murderer of his late brother’s wife. Naturally for a work opposed to not taking advantage of any dramatic possibility it can, Jake once had an affair with her. Silva’s volatile adult son (George Steane) is also the prime suspect.

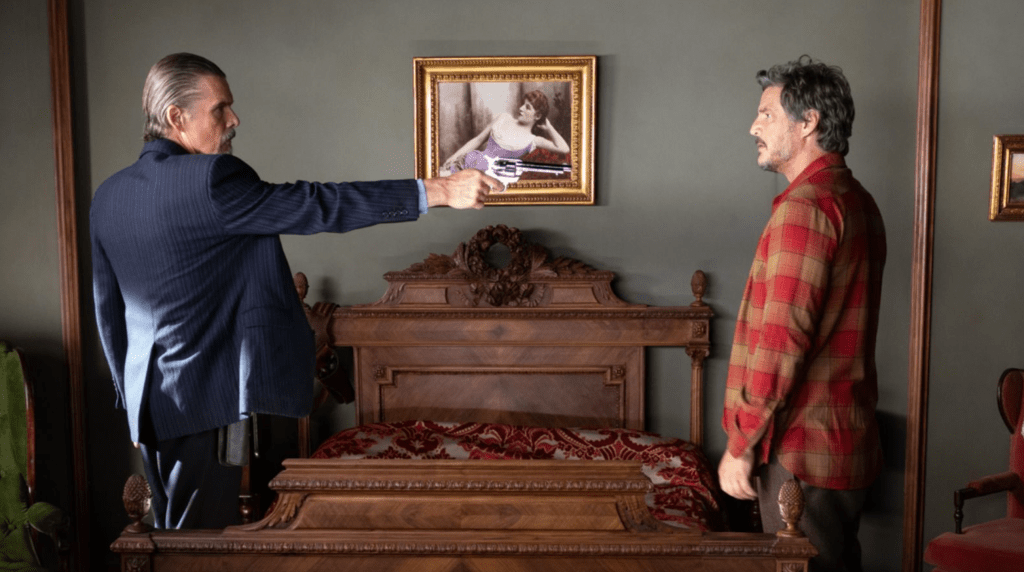

Jake and Silva initially indulge their old lust. But once morning comes, the night before teased with Silva sleeping prone and pantless among rumpled sheets, their accord cracks. Seeing their reunion as a sort of cosmic sign, Silva wants to get back together — to see through the abandoned, nearly three-decade-old plans to run a business together at a shared ranch to shield their forbidden love. Jake, who speaks almost exclusively in a pained whisper, would prefer this remain a one-off relegated, like his and Silva’s time together 25 years ago, to a cherished secret. The red curtains blotting out the light coming in from Jake’s bedroom windows give the exchange a certain theatrical immensity.

Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal in Strange Way of Life. Photography courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Where, exactly, these men stand in each other’s lives will be again tested once they separately, inevitably, catch up with Silva’s wanted son. It will become less a matter of who will shoot whom and more how someone will shoot another, and the consequences expected from that decision. Strange Way of Life’s ending is neatly poignant, and it speaks to what this short is best at: not at being overheated, which it is in rather silly bursts, but at being tender, about which it is a little more hesitant — in keeping with the never-specified but clear-enough time period in which it’s set. That doesn’t apply, of course, to the visuals, which, though muting Almodóvar’s usual proclivities for the vibrantly kaleidoscope, are most memorable when they’re loudest: the punchy sea-foam green of the jacket in which Silva arrives in town, the gold frame of the painting above Jake’s bed in which a woman lounges in a plum-purple dress.

Cameras cut away when the first signs of desire emerge; the most direct eroticism in the movie comes courtesy of the sexy, briefly seen younger versions of Jake and Silva, able to lose themselves in a wine-drenched cellar makeout session both because they’re certain that they’re alone and are also, because they’re barely into their 20s, not thinking about what could follow. (As for their older analogs: tasteful, slow-motion close-ups of their longing faces while they reacquaint themselves in bed.) The tameness with which Strange Way of Life’s sexuality is depicted may be overarchingly complementary to the secrecy with which these men have had to live. But it’s also disappointing for a piece ostensibly wanting to not merely disrupt the unyielding visions of straight masculinity as typically seen in the Western, but also to make explicit the genre’s often flaring but usually only implicitly expressed homoeroticism.

The more-weathered men we meet in Strange Way of Life have metabolized their earlier experience differently. Jake stalls with shame; Silva has lived long enough to know that he’d rather a “shameful” part of himself tangibly live on in secrecy than remain only a memory, a desire far out of reach. We want more time with these men as they try to make sense of feelings lent new urgency now that the person at the crux of them is now back in their lives. But what we get is so fleeting in Strange Way of Life that whatever pathos they rouse feels clipped. There’s a feeling when it ends that the journey is over just when we’ve gotten on the road.