Nothing in Pedro Almodóvar’s wintry English-language feature debut, The Room Next Door, wins you over as much as the proportionally stylish and cozy-looking clothes its leads, Julianne Moore and Tilda Swinton, wear. A celebrated stylist who knows which color combinations do and don’t work better than most people, Almodóvar largely puts Moore in purples and greens that elevate her trademark red hair into a supporting character. Swinton, an actress likened more often than any of her peers to an alien or glam-era David Bowie, hogs all the look-at-me shades foolproof at seizing your eyes: a bright teal quarter-zip, a canary-yellow suit jacket, a Hubba-Bubba-pink robe. The film’s sartorial centerpiece is probably the cartoonishly slouchy, red-, yellow-, blue-, and gray-blocked Loewe sweater Swinton wears for the occasion of crying to her character’s favorite movie. (Swinton brought it from her personal collection to the movie’s shoot at Almodóvar’s behest.)

A sensation common in all of Almodóvar’s films, it’s an easy pleasure to simply ogle The Room Next Door’s surfaces, which so comprehensively pop with color that the occasional intrusion of something bland — gray, beige — almost strikes you as offensive. But how Almodóvar’s movies look is not really the primary draw. When he’s at his best — All About My Mother (1999), Volver (2006), Pain & Glory (2019), to name a few of his masterworks — his signature visual world serves as an amplifier to, depending on the mode he’s operating in, breathlessly emotional stories in the Douglas Sirk mold or chaotic comedic situations that rival the great screwball comedies. You tend to be as seriously absorbed as actively delighted when an Almodóvar movie is fully working.

So it’s strange to encounter one as airless as The Room Next Door, particularly since it’s coming in the wake of a previous few years widely agreed to be a sort of return to form following a string of underwhelming projects that made you nostalgic for past glories. True, it’s among the filmmaker’s most somber movies — about a former war correspondent, Martha (Swinton), who’s in the third stage of a cervical-cancer battle and decides she’d prefer to euthanize herself with a black-market pill to withering away. The title refers to the space in which she has the old friend she’s recently reconnected with, a celebrated fiction writer named Ingrid (Moore), stay in the plush Upstate New York house she’s renting to spend her final days.

The Room Next Door feels like something of a cousin of Pain & Glory, a faintly autobiographical movie where Almodóvar muse Antonio Banderas played an aging director whose physical decline has prompted a reflection on his life’s triumphs and regrets. But while Pain & Glory practically thrummed with melancholy, cyclically inviting tears, The Room Next Door is chronically inert. The frosty dialogue is unnaturally literate and overexpository, particularly when relating to personal histories and philosophies (though that could be a language-barrier thing). Further impaired by a puzzling reticence around their characters’ shared histories, Swinton and Moore’s friend chemistry is so labored that these ostensibly tight-knit characters who are meant to have been in and out of each other’s lives for years seem only to have just met. (The actresses’ conversations can unfurl so woodenly that my boyfriend and I wondered, with a little laughter, whether some scenes had been dubbed after the fact.) In Almodóvar’s other mortality-concerned movies, a sense of life burst despite its looming end. Unusually for a director who’s pretty much always made films that feel like the screen can barely contain them, The Room Next Door maintains the distance of a hypothetical.

Vic Carmen Sonne in The Girl with the Needle. Courtesy of MUBI.

This is what knitting-factory worker Karoline (Vic Carmen Sonne) goes through in the first half-hour or so of Magnus von Horn’s nauseatingly riveting The Girl with the Needle: she loses her apartment; gets knocked up by a boss who says he’ll marry her; has the engagement reneged once his tyrannical mother gets involved; gets promptly fired from her job; tries and fails to give herself a knitting-needle abortion in a public bath. And she can’t even hope, as a fallback, that the husband she figures has been killed in action — the Copenhagen-set film begins around the time World War I is ending — to maybe come back and help her get back on her feet. He does return early into The Girl with the Needle, but she tells her newly disfigured one-time beau that she wants nothing to do with him because she’s so certain she has a new life on the way.

We know things are unlikely to get much better after that. This is a movie shot in the type of high-contrast black and white that would be just as well-suited to a vampire movie. And if you’ve cursorily looked into what the film is about, you’ll at least know that part of its narrative pulls from the real-life crimes of Dagmar Overbye, who across the 1910s clandestinely operated as a serial killer who rationalized her queasy modus operandi as not particularly dissimilar from a social service. How she becomes a motivating force in Karoline’s life epitomizes how if Karoline seems to stumble on some good fortune in one moment, it seems predestined to go bad in another.

The Girl with the Needle is a horror movie — though von Horn has been more comfortable framing it in interviews as a dark fairy tale — yet it’s not, as might be expected, that gung-ho about making Dagmar a thoroughly wicked figure à la Dracula. She’s a complex product of a society whose cruelty to women knows no bounds, doing what she sees as a necessary kind of assistance for peers imprisoned by miserable, patriarchy-defined circumstances over which they have little control. Trine Dyrholm is chilling as the often inscrutable Overbye. Sonne, the kind of actress preternaturally good at saying a lot with her eyes, gives one of the year’s great performances as a practically cursed young woman who’s come to live for nothing besides precarious survival.

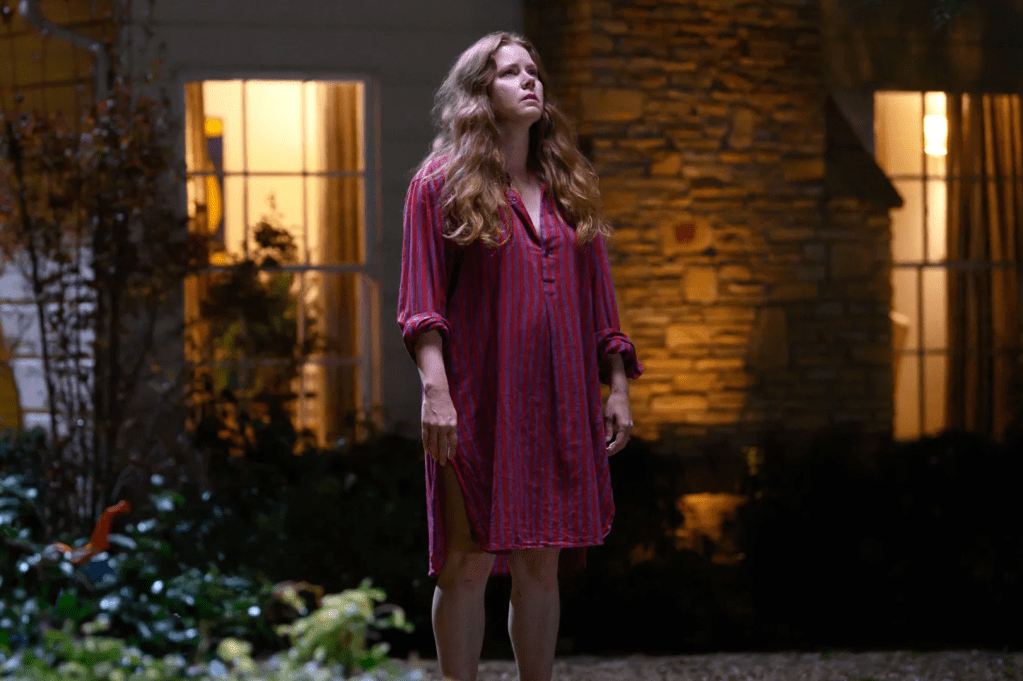

Amy Adams in Nightbitch. Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures.

I haven’t read Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch, but I can tell it probably worked better on the page than writer-director Marielle Heller’s new adaptation does on screen. It has a kooky premise — a revered, never-named multimedia artist turned stay-at-home mom becomes convinced that in her haze of maternal malaise she’s turning into a dog — that in the movie feels like a gratuitous appendage to a series of well-observed scenes of domestic frustration. (You can keenly feel what Heller’s meant when she’s talked about seeing much of herself in her protagonist.)

Nightbitch is effective when it’s wallowing in ordinary-but-no-less-purgatorial parental misery, which has become such a choking fog for its heroine that she frankly tells her well-meaning but aggravatingly clueless husband (Scoot McNairy) that she always “feels like I’m on suicide watch.” When the movie’s gimmick has to be underscored — the mother character, played by a terrific-as-ever (and importantly very committed) Amy Adams, popping a cyst only to find a tail curling out from the drippy puss, or tearing into a meal face-first — you’re almost taken out of the movie for being so at odds with the productive, naturalistic discomfort Heller sharply creates elsewhere. The pat finale widens the chasm, making this movie that would have benefitted from being darker and weirder feel like it’s backed off with a whimper before it could have done something as bold as we might have hoped for.