Babygirl made me nostalgic for that brief period in the aughts when Nicole Kidman was consistently starring in daring, sometimes hard-to-embrace films — the rare bonafide movie star who was as much willing to devote her time to more commercially viable work as to arthouse directors giving her license to let her freak flag fly. Kidman remains game to do basically anything, but of late she’s been a little more partial to disposable beach-read projects that feel slightly beneath her, to a degree that might make one yearn for the time when she was more excitingly unpredictable than fairly easy to pigeonhole.

Babygirl is a welcome respite from normie Kidman. The third feature from the actress-turned-filmmaker Halina Reijn — whose last movie, the housebound ensemble comedy Bodies Bodies Bodies, was a darkly funny highlight of 2022 — casts Kidman as Romy, the high-powered CEO of a vaguely defined robotics company who starts a BDSM-inflected affair with a much-younger, rakishly cute intern named Samuel (Harris Dickinson). Both Romy and Samuel, who first disarms his superior by questioning her in front of a crowd, are hyper-aware of how inappropriate their rendezvouses are, bringing up the dramatically uneven power dynamic, and each person’s nearly click-of-a-button ability to destroy the other’s life and career if things sour, more than once.

But for both, that’s part of the appeal. Romy briefly adverts to growing up in a cult, and it’s suggested that those developmental years are partially responsible for making it so that she isn’t truly satisfied sexually if she isn’t being told what to do — if her sex life doesn’t come with high stakes. It’s no wonder that, after the film’s opening sex scene with her hot theater-director husband (Antonio Banderas), with whom she has a couple daughters (Esther McGregor and Vaughan Reilly), Romy heads to a different room post-fake climax to furtively get off to some porn better serving her fantasies.

Nicole Kidman and Harris Dickinson in Babygirl. Photo by Niko Tavernise.

Babygirl has frequently been described by critics as an erotic thriller. It shares much of the genre’s DNA, namely sex laced with life-ruining potential and glossy production design visually consonant with the wealth of its usually well-off, comfortable-in-life characters. But unlike the tentpole examples of the genre — say, Fatal Attraction (1987) or Disclosure (1994), which share Babygirl’s workplace centrality — Reijn invigoratingly does away with its typically inexorable moralizing and family-first conclusions. Instead she relishes in the forbidden fun of a woman who has it all exploring a part of herself dormant for the duration of a 19-year marriage during which she’s never orgasmed. (Romy doesn’t even feel like she can bring up experimenting in bed to her spouse without bashfully covering her face with a sheet.)

Kidman is thrilling to watch as a seemingly indomitable woman her assistant (Sophie Wilde) jokes was raised either “by soldiers or robots” surrendering to an affair to which she initially resists fully committing. Dickinson is, too, as a young man who seems a little tickled about pulling this off, a pleased-with-himself grin slipping a few times whether he means to or not. His character never, as we might suspect early on, transforms into a blank-from-hell character the erotic thriller helped popularize. The subversive Babygirl is just fine wondering what might happen if “the villain trying to destroy your life is your own misspent masochism,” as the critic Miriam Bale recently posited.

That subversiveness extends to where the movie climatically goes, which does feature a requisite showdown but, like so much else in the film, only flirts with its genre ancestors’ moralizing characteristics without fully recapitulating them. It’s having too good a time following this anti-heroine as she sees her potentially destructive instincts through, and makes a convincing case that blowing up your life can have its benefits. It’s the only erotic thriller I can think of that I want to call touching as much as I do sexy.

Pamela Anderson in The Last Showgirl. Courtesy of Roadside Attractions.

I’m glad we got a movie out of this time of Pamela Anderson appreciation even if it isn’t very good. In The Last Showgirl, she plays the woman the title refers to, a 57-year-old with a sweet gee-whiz disposition named Shelly. Shelly has worked for nearly 40 years as a key player in a kitschy Las Vegas revue her semi-estranged daughter (Billie Lourd) unamusedly calls “a stupid nudie show,” but she doesn’t mind it if what she does isn’t considered high art. It’s good enough for her to have spent countless nights bathed “in that light, feeling seen, feeling beautiful.” Shelly would happily expend the rest of her days at this place she’s committed more than half her life to, but changing times oust her soon after the film opens. The building’s owners think something flashier — in their case a more economical version of a Cirque du Soleil-style show — would make more money than this rather sleazy performance whose heyday peaked around the time Shelly vamped for promotional photos in the late 1980s. Shelly and her younger co-workers — a couple of whom (Kiernan Shipka and Brenda Song) look up to her like the mother figure she’d prefer not to be — have only a couple of weeks to figure out what’s next.

How do you restart your life after getting comfortable with the one you’ve had as long as Shelly has? Anderson is immediately affecting in this made-for-her role that naturally parallels her own status as a bombshell squarely in middle age. But writer Kate Gersten and director Gia Coppola can’t help but carve out what little of a story they have with overly-worked-out pathos and a vantage point that can’t shed a feeling of outsiders-looking-in condescension. The nadir is a scene where a down-and-out friend of Shelly’s, a former showgirl turned perpetually sloshed cocktail waitress with a bad dye job named Annette, dances suggestively for disinterested casino patrons to Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart” (1983) — a gratuitous moment of reattempted former glory that might have been meant to inspire compassion but mostly just feels patronizing. (Jamie Lee Curtis’ performance as Annette — one of many trailing her undeserved Everything Everywhere All at Once Oscar win that has taught her incorrectly that she should vie for big-and-broad parts more often — is also unhelpfully terrible.)

The Last Showgirl is worth watching because Anderson is not merely in it but actively good, heartache-inducing every time Shelly so much as laughs or smiles through her obvious pain. Anderson is a saving grace for a movie that feels like, after the embarrassing, out-of-touch social-media satire Mainstream (2021), more fodder for the argument that Coppola’s feature debut, the understated teen movie Palo Alto (2013), was a fluke. The Last Showgirl isn’t obnoxious like Mainstream, but both movies have a clodding touch that makes everything feel overdetermined, angling for profundity so hungrily that all you can do is feel how much they’re trying. But despite the shortcomings of her director, Anderson still moves me in the many meant-to-be-lyrical, excessively soft-focus shots where she’s gazing plaintively at the city she once felt on top of.

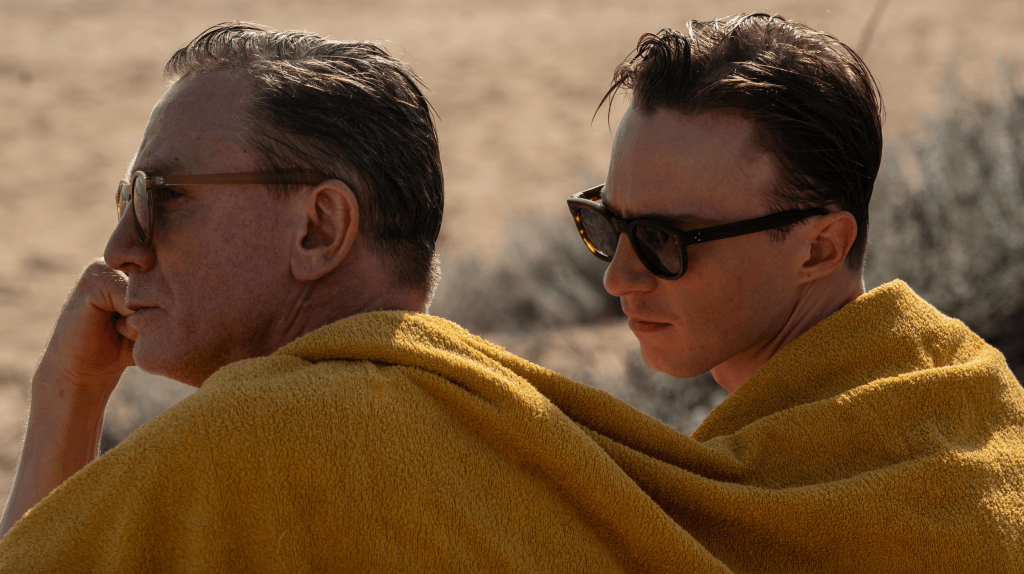

Daniel Craig and Drew Starkey in Queer.

I much prefer Luca Guadagnino’s other movie of 2024, the steamy sports soap Challengers, to Queer, but since seeing Challengers was probably the most fun I had in a theater all year, it was probably going to be eclipsed regardless. This comparatively subdued adaptation (by Challengers scribe Justin Kuritzkes) of William S. Burroughs’ same-named novel is nevertheless a pretty vivid evocation of gay longing, particularly when it’s burdened with caveats like societal repression and unreturned affection.

The man doing the longing in the early 1950s-set Queer is William (Daniel Craig), a Mexico City-based expatriate who does little every day but drink, do heroin, cruise, and shoot the shit with a small contingent of other American gay men who too have defected there. (A sweaty, schlubbified Jason Schwartzman is very funny as the only one in the mix who gets much of a speaking role.) The object of William’s affection is Eugene (Drew Starkey), a much-younger, recently discharged sailor he sees for the first time on the fringe of a crowd watching a streetside cockfight. William’s pining isn’t entirely one-sided — the pair will eventually fall into an affair — but it’s clear from the jump that their relationship will likely not survive past the short-term, what with William’s temperamental, sometimes exhaustingly loquacious personality and Eugene’s unflagging inscrutability. (I’ve read complaints of Starkey’s performance being bland, but I think that temperance is perfect for an enigmatic, achingly pretty character that Lee never fully gets to know, is never able to gaze at without his projections snuffing out hard-to-swallow truths.)

The wandering Queer’s style is less boisterous than Challengers’. But it’s still full of the kinds of distinctly Guadagninian choices that ensure this all feels a little prettier, a little more cinematic than life or Burroughs’ dark, mercurial prose: anachronistic needle drops (there are many eye-roll-inducing cuts from Prince and from Nirvana, whose Kurt Cobain admired Burroughs), and clever uses of miniatures, sumptuously artificial lighting that recall what was being done generations earlier by pioneering gay filmmakers like Kenneth Anger and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. (There’s a sprinkling of surrealism to match Burroughs’ own unwieldy style, too, which brings with it some undercooked allusions to the writer’s ostensibly accidental 1951 killing of his wife, Joan Vollmer.) Few of Guadagnino’s aesthetic tricks worked on me nearly as well as his showing, through phantom-like visuals, what William would like to do to Eugene, whether it’s a kiss or a touch, in certain moments but for whatever reason — his nerves, the environment they’re in — finds himself unable to. Sometimes Guadagnino’s flashiness is for its own sake, and sometimes it speaks to a moment’s feeling better than words or the naked eye could.