It’s been nearly a decade since the release of Jackie (2016), the Jacqueline Kennedy-centric first part of a Pablo Larraín-directed trilogy focused on iconic women public figures linked together by the claustrophobia of their lives and the outside narratives foisted on them. With a predilection for disorienting close-ups and a cacophonous Mica Levi score, Jackie made the immediate aftermath of John F. Kennedy’s assassination as it was experienced by his widow (Natalie Portman) feel not dissimilar from a horror movie. Its spiritual follow-up, the Princess Diana-focused Spencer (2021), continued in the same notoriety-as-suffocation mode, using a short, painful period in its subject’s life as emotionally representative of longer-term miseries and struggle.

I agree with the complaints often lodged at these movies — that they’re better at aesthetically doing justice to personal malaise than at actually wrestling with it meaningfully; that they too liberally minimize their subjects to their suffering — while also finding them viscerally effective enough to be worthwhile as emotionally speculative fiction. The newly released final chapter of the trilogy, which revolves around the opera great Maria Callas, marked a departure for me. Those aforementioned complaints are again easy to concede to, but there isn’t much more to redeem them except for Angelina Jolie’s fragilely grand performance as a singer not yet ready to rest on her laurels in the way her prematurely frayed voice would prefer her to.

Though it is, like its predecessors, not averse to flashbacks (there are many, shot in pearlescent fashion-spread black-and-white, generally inclined to revisit her doomed love affair with the self-described ugly-but-rich magnate Aristotle Onassis), Maria’s action is largely confined to the week before its subject’s untimely death in the fall of 1977. Callas is only 53 but reclusively living in her sparsely decorated Parisian apartment like someone much older. It’s been four and a half years since she last sang live, an absence spurred by a suddenly unreliable voice that has in turn inspired even her most devoted fans to jeer. She basically only ever sees her protective, ever-dutiful butler and housemaid (Pierfrancesco Favino and Alba Rohrwacher), both of whom she a little toxically views less as employees than family, and mostly exists within Quaalude-induced hallucinations she’s come to appreciate as “revelations,” “theater behind my eyes.” She only eats every three or four days, or maybe she’s discreetly slipping meals to her dogs while the maid’s back is turned.

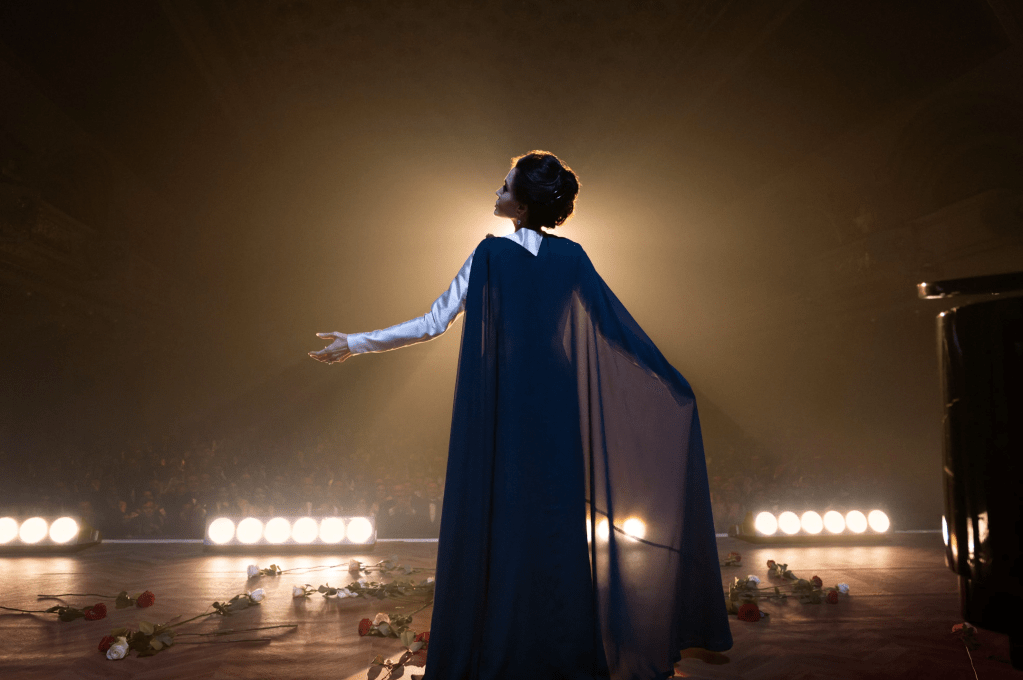

Angelina Jolie in Maria. All Maria imagery courtesy of Netflix.

Cinematographer Edward Lachman gives everything a coppery, slightly on-the-nose veneer that outwardly suggests Callas’ internal decay — the dimming outlook of a woman who’s lost her lust for life and rapidly losing her health, too. (Callas’ voice, for what it’s worth, isn’t completely gone in Maria — she’s wont to give an unsolicited “show” in her kitchen one morning, to which the breakfast-making help will obligatorily call “magnificent” — but even those in her circle trying to help mount an ill-fated comeback can’t help but observe that “that was Maria singing; I want to hear La Callas.”)

Jolie practically glides in thick furs and dramatically trailing coats matching a long and luscious head of gray-streaked hair. Oversized glasses magnify the inky contacts worn to imitate the stormy, cat-like ones of the woman she plays. (Jolie looks incredible even when she doesn’t want to get out of bed.) This version of Callas, as written by Steven Knight, speaks almost exclusively in statements both befitting of its subject’s augustness and a little silly. (“I’m not hungry — I come to restaurants to be adored”; “My mother made me sing; Onassis forbade me to sing; now I sing for myself”; “There is a very common theory that if you ask for something, you want it — but that is not true.”) But Jolie nails the appropriate tone in her delivery: sometimes exhausting-to-be-around divadom that can’t conceal the anguish gnawing away at her. And though she doesn’t look much like Callas, the outsized nature of the actress’s own public persona is apt for someone so titanous in life and death.

Angelina Jolie in Maria.

I appreciate Larraín’s consistent avoidance of hagiography and larger biopic conventions in his iconic-women trilogy. But Maria is presented so fussily — there are all the flashbacks, the gratuitous element of a hallucinated, Kodi Smit-McPhee-led TV crew conveniently allowing Callas to touch on autobiographical details that otherwise wouldn’t necessarily be discussed in her day-to-day life — that I sometimes noticed that I wouldn’t have been opposed to a more straightforward rise-and-fall narrative or, if not that, a commitment to staying put in one timeline and making peace with biographical elisions. Maria is too busy to ever completely absorb you in anything.

Callas doesn’t make much sense as a figure in this trilogy. It’s elsewhere about women whose ascent to the parasitic public eye, and their subsequent maintenance of their status, was ushered in by powerful men, and how hard that could be to live with both in the home and in public. Callas’ relationship with Onassis, depicted in the movie so airlessly that you can’t smell even a hint of why they were together for nearly a decade, might have been a defining part of her life, but isn’t as much raveled in the public’s conception of her the way Jackie and Diana were associated with their husbands. Callas’ artistic mastery was, and continues to be, foregrounded in people’s minds. It feels almost diminishing, given her one-of-one talent, to put her in the same conversation as the other women in the trilogy, whose accomplishments aren’t commensurate to Callas’ own.

Maria nonetheless pretty decently portrays how much it can feel like waking death to live for nothing but your art only to not have the same access to it the way you once did. Still, I couldn’t help but continuously itch for a movie that engaged with Callas’ artistry as more than mainly a source of soul-crushing misery, that didn’t so forcefully and finitely “frame Callas’ life as tragic,” as Callas biographer Daisy Goodwin recently put it. Larraín’s trilogy as much makes you see his subjects in a new light as aware of the restrictions of his gaze.

Adrien Brody and Felicity Jones in The Brutalist. Courtesy of A24.

The Brutalist, Brady Corbet’s new movie, is the kind of epic drama that increasingly feels like a vestige of the last century. It’s about three and a half hours long, with a 15-minute intermission built in, and could simplistically be described as a movie about the American dream. (It also harkens to the past by being lustrously shot by Corbet’s favored cinematographer, Lol Crawley, in VistaVision, a striking widescreen photographic process Paramount briefly used in the 1950s that gives color a romantically faded, almost watercolored melancholy.) It’s a movie one could admire for its ambitiousness alone, but there thankfully is much more to appreciate in this film that strikingly grapples with the distressed relationship between art and capitalism and the tacit rules and limitations one must adhere to, by choice or not, to truly succeed in America.

Co-written by Corbet and Mona Fastvold, The Brutalist spans decades (it begins just as World War II is ending) and follows a fictional Hungarian Jewish architect, László (a tremendous Adrien Brody), who is forced to start his life anew, without the niece (Raffey Cassidy) and wife (an excellent Felicity Jones) from whom he was forcibly separated and with whom he will ultimately be reunited, when he immigrates to Philadelphia to live with his furniture store-owner cousin, Attila (Alessandro Nivola), and his prissy wife (Emma Laird). László was much-celebrated before the Holocaust; his career was dashed by a Nazi Party that didn’t find his favored Bauhaus-trained brutalist style “Germanic enough.” After years of struggle and false starts, he’s eventually championed in his new home by a mustachioed industrialist with an inferiority complex (Guy Pearce) who sees the designer as a means to bolster his craved image as a living giant through imposing architectural pieces.

This only is a thin outline of a dramatically supple, uniformly well-acted movie that, like Corbet’s last film, the broad-targeted pop-industrial-complex commentary Vox Lux (2018), takes a commendably big swing but, unlike the disastrous Vox Lux, is knife-sharp, finding gradual power in patient, increasingly nauseous accumulation — a value I wish I saw in more new releases.