Even in his lesser works, Wes Anderson’s famously fussed-over aesthetic has always been easy to appreciate for a level of down-to-the-infinitesimal attention to visual detail that can make other looks-first filmmakers seem sloppy by comparison. While watching his newest movie, the Cannes-fresh The Phoenician Scheme, it invigorated me anew for no reason I can think of besides the contemporary rise of artificial intelligence, which has increasingly instigated distrust in what’s seen and read. As the distinctiveness of artistic human touch continues to be technologically polluted and taken for granted, it’s almost soothing to watch the work of a filmmaker who near-fetishistically celebrates stylistic precision and tactility.

The newfound thrills of Anderson’s manicured style cannot, though, free The Phoenician Scheme from a problem afflicting his movies since, arguably, The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014): the feeling of his aesthetic being so oppressive that the performances and emotional lives within become flattened. It would be inaccurate to describe Anderson as a style-over-substance director. It’s more that his style weighs down his substance.

The Phoenician Scheme has plenty of the latter. The 1950-set movie is rudimentarily about a corrupted, much-despised tycoon, Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro), trying desperately to win back the love of his estranged 20-year-old daughter, Liesl (Mia Threapleton), who’s on track to become a nun. Part of the reason for his interest in reconnection, though, is brought on by his worry — the movie opens with an assassination attempt via plane crash he very nearly doesn’t survive — that one of his endless enemies will off him before he can see through an ultra-ambitious construction project he has for the fictional country of Phoenicia.

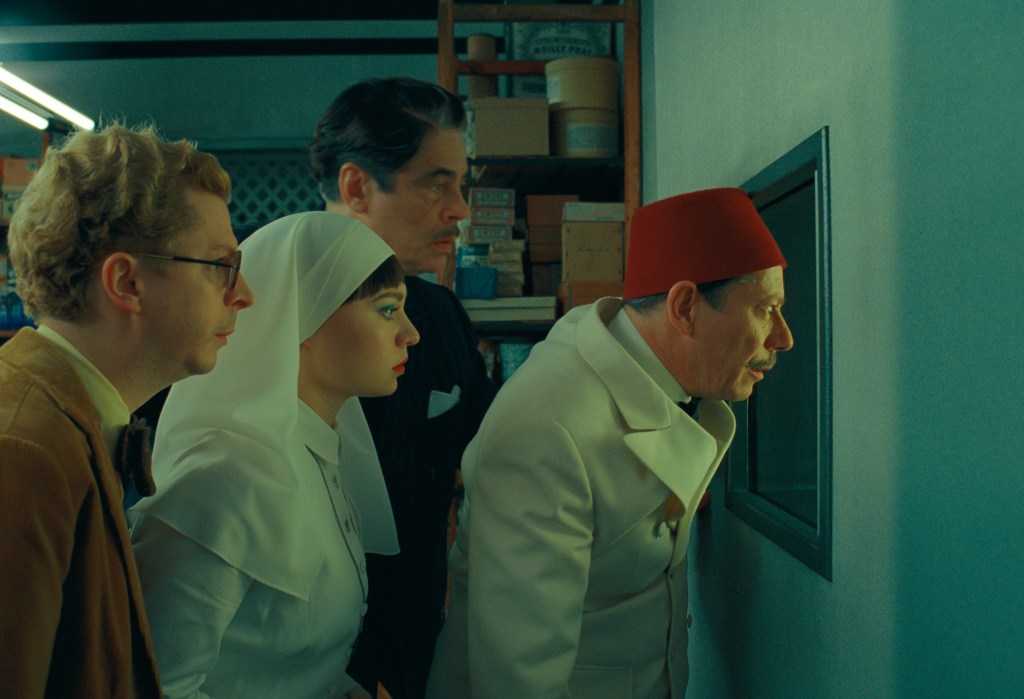

Michael Cera, Mia Threapleton, Benicio Del Toro, and Mathieu Amalric in The Phoenician Scheme. Both photos courtesy of TPS Productions/Focus Features.

The movie encompasses several trips to far-flung locales — Liesl and Korda’s administrative assistant and tutor, Bjørn Lund (Michael Cera), remain at his side for all of them— for the purpose of business dealings with characters played by many of the high-price-tag actors who are part of Anderson’s stable. Tom Hanks, Jeffrey Wright, Scarlett Johansson, Riz Ahmed, and Benedict Cumberbatch are among them. Bill Murray, Charlotte Gainsbourg, and Willem Dafoe also appear in austerely shot black-and-white fantasy sequences supposedly set in Heaven, into whose sky-high bliss Korda might not be welcome.

Every exchange is as deadpan as you’d expect from Anderson; explosions of violence are treated with the same placidity as the monotonous passing of time on a long airplane ride. Every actor is near-completely robot-stiff, their gestures choreographed to the hilt. (The way Hanks holds a chocolate bar or Bryan Cranston clutches a bottle of Coke, for instance, bear Anderson’s marks of exactitude.) There’s some pleasure in seeing movie stars so thoroughly molded by a director asking for a sort of arch woodenness never requested from them. It can also be tedious to watch a movie so star-studded packed with performances that are, disparate costuming and accents aside, barely distinctive from one another, immured by their living-statue restrictions.

A newcomer who until a few years ago had been best known as Kate Winslet’s daughter, paper doll-faced Threapleton emerges as the finest thing about The Phoenician Scheme because, when applied to someone unfamiliar, Anderson’s meticulous direction of actors can make the resulting work feel less like a self-conscious pose and more a venue to illuminate a specialness that might not have yet been captured in a just-starting career. There’s an understated, playful wink to Threapleton’s performance even if I didn’t once catch her face move out from the unamused rictus in which it’s perpetually frozen. I wish more of The Phoenician Scheme didn’t have the smothered quality her work nimbly manages to skirt.