Brian De Palma didn’t invent the split-screen editing technique, but its tension–maximizing use across several of his movies has arguably made him the filmmaker most associated with it. His first truly indelible deployment of it happened in Sisters (1972), a Hitchcock-inspired horror movie involving once-conjoined twins who have more than a little dysfunctionally gone their separate ways. Split screen is employed on a sweaty early sequence where one frame is taken up with the point of view of a murderer cleaning up the aftermath of a kill, the other the vantage of a nosy neighbor who first calls the police to unload what she’s just witnessed before deciding to take matters into her own hands.

Writer-director-producer James Sweeney uses De Palmian split screen in his identical twin-preoccupied second project, Twinless, soon enough to make you nervously wonder whether it’s going to devolve into frenzied, antic horror à la Sisters. It does not — its terrors are, aside from the bloody ways two characters die in tragic accidents, strictly emotional and psychological — and it might make you yearn for more boldness than it ultimately offers beyond its auspicious first act.

The Portland-set, persuasively lonely-feeling Twinless was a word-of-mouth hit at both this year’s Seattle International and Sundance Film Festivals. It seems to me now that the reality-warping atmosphere of those kinds of events — where one is bombarded with so many underwhelming movies that one becomes far more enthusiastic about not-that-bad features they might not have been in the context of an average opening weekend — has probably set too high of expectations for a stylishly made, fitfully clever movie that largely mistakes the “‘novelty’ of its premise for profundity,” as Nick Dets has written.

Dylan O’Brien and James Sweeney in Twinless. All Twinless imagery courtesy of Roadside Attractions.

Twinless’ conceit is undoubtedly original. It’s about — spoilers ahead — a waifish, socially stunted loner, Dennis (Sweeney), who, after a one-night stand with a mustachioed man named Rocky (Dylan O’Brien), befriends his straight, identical-twin brother, Roman, after Rocky is hit and killed by a car. How Dennis makes that connection is contingent on a squirmy amount of deception, though. Seeing Roman from afar one evening, he follows him into a bereavement group for twins who have lost their other half — a rather niche support-group category for which I was surprised there were enough members to fill a meeting space — and pretends like he, too, is now sans brother. He never mentions his romantic dalliance with Rocky, or, more understandably, that he could be said to be indirectly responsible for his death. The latter might not have stepped into the street without looking both ways had a spurned, hoping-for-more Dennis not been stalking him, calling out for his transitory lover’s attention after a short period of what seemed like ghosting.

Roman and Dennis’ anguished bond is humorously built mostly on joint grocery runs and listless at-home hang-outs where the high of an evening might be finding out how many marshmallows the other can cram into their mouth. In this movie that tracks how far the trickery can go in this blooming bromance, Roman comes to see Dennis as a friend. Dennis’ attachment is inevitably more fraught, blemished by his use of Roman as a proxy for Rocky and the power he reaps from being the only one in the know about the deception.

Dylan O’Brien and James Sweeney in Twinless.

O’Brien is very good in Twinless. The movie’s finest scene sees his character using Dennis, with heartrending intensity, as a sounding board to temporarily relieve him of the bottled-up complexities of his sorrow — the way his love for his sibling is also stained with petty jealousies and never-fully-atoned-for regret around his past homophobia. O’Brien also does something Michael B. Jordan, as Hunter Harris cheekily declared recently, did well in this year’s Sinners: making one twin hotter than the other. Even if he a little on-the-nosely has a Freddie Mercury-esque style of dress and has a lispiness that’s faintly disconcerting when it’s coming from the mouth of a playing-gay straight actor, Rocky is cocksure and charming. Sweeney gives you just enough of the character in flashback that you have a firm handle on the flash-bang impact he had on Dennis’ life and how it could be so difficult to move on from from his lovesick perspective.

O’Brien can do a lot with that brevity; it doesn’t take long to wish it were Roman’s experiences the movie primarily orbited around. Sweeney isn’t as strong a performer as his co-star. His writing and direction would be superficially emotional and crafty regardless of whether he was in front of the camera. In addition to the abundance of mirrors, all the clobberingly obvious touches would remain: the opening of a Pop-Tarts package missing its expected second serving; passing more than three sets of identical twins within a single city block; using Haim’s “Leaning on You” to soundtrack a montage capturing Roman and Dennis’ new, fortifying friendship. But Twinless is more bothersomely prodded with the sense that a seasoned actor at its nucleus would have made it a markedly more convincing movie. Like other writer-director-stars — Woody Allen, Xavier Dolan, his more-recently-emerging peer Cooper Raiff — Sweeney’s work as an actor seethes with distracting self-consciousness.

He seems so worried about inadvertently flattering himself too much — lest there be the kind of self-fawning accusations common among detractors of Raiff’s last movie, 2022’s Cha Cha Real Smooth — that the abandonment issue-haunted Dennis becomes unbearable to be around. He ought to have been something more appropriate for the movie’s aims: inexcusably, but also pretty sympathetically, reckless. Sweeney keeps sympathy for his character too distant, something regularly furthered by his resentment-marinated meanness toward a perfectly nice co-worker (a note-perfect Aisling Franciosi) that eventually starts up a romance with Roman. The inexorable “big scene” — the one where Dennis’ duplicity surfaces — thuds, even if the brazen gesture that precedes it is grossly funny and effective. Sweeney’s limitations as an actor are here most overpowering; they capsulize the movie’s larger slightness.

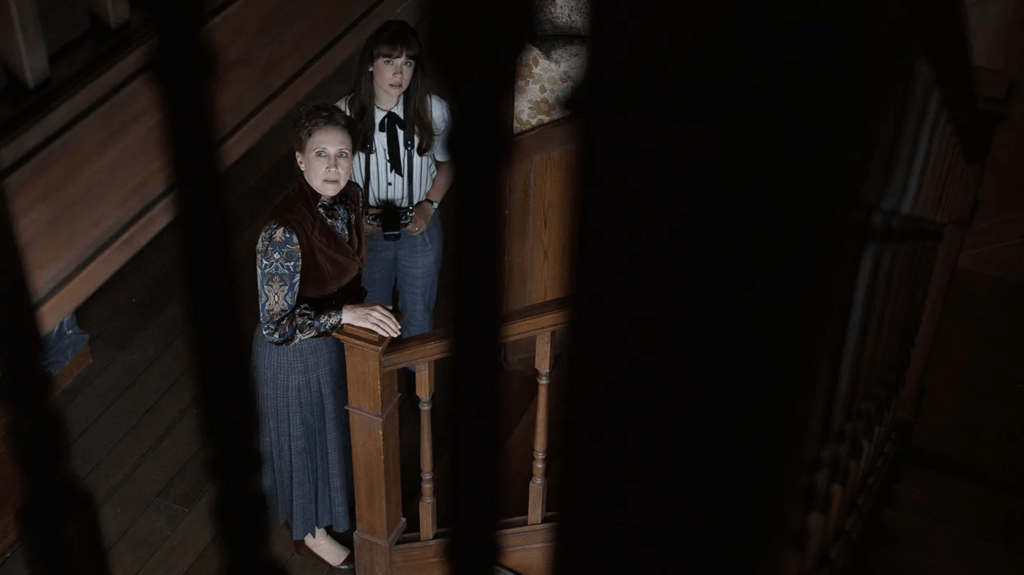

Vera Farmiga and Mia Tomlinson in The Conjuring: Last Rites. Courtesy of Giles Keyte/Warner Bros.

Despite their irresponsible image remediation of quack paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren, the increasingly worse movies comprising the Conjuring series have all been effective-enough haunted-house films with a certain family-friendliness that recalls the spookier-than-scary Poltergeist (1982). The decades-spanning saga’s latest chapter, Last Rites, is posed as its last, zeroing in on a 1980s case in Pennsylvania. (It marks a return to the sort of demons-haunting-a-big-family premises of the first couple movies after the third film, the scare-parched The Devil Made Me Do It, mostly confined the Warrens to quasi-detective work following a supposedly possession-triggered murder.)

Last Rites cares more about giving an emotionally satisfying send-off to its fantasy versions of the Vera Farmiga- and Patrick Wilson-portrayed Warrens — kinder and foxier than their real-life counterparts — than its investigation-prompting family. So it’s slower to get to the showy climax on which the success of these movies pretty much hinges. (Last Rites’ feels like it’s going through the motions.) For most of its runtime, the film oscillates between the bumps in the night its spirits-vexed family suffers through — there’s some decent stuff with an electronically babbling baby doll and a painstakingly rewound home video to double-check suspicions of a ghoul appearing in it — and intermittently chills-interrupted check-ins with the Warrens.

Their arc is most concerned with their now-grown daughter, Judy (Mia Tomlinson), who’s inherited her mother’s seer gifts, and her marriage-destined romance with former cop Tony (Ben Hardy). The pair is no doubt being introduced to test the waters for a possible Marvel-esque Phase Two where they can be Ed and Lorraine Jrs. Expanding the “universe” of the original Conjuring movie, which came out in 2013, has been a profitable endeavor; even the spin-offs — revolving around the Chucky-like doll Annabelle and a demonic nun who strangely doesn’t actually show up much in the movies named after her — have their own sequels.)

The Warrens, as the film opens, swear they’re retired from paranormal sleuthing, owing mostly to Ed’s fragile heart health. They’re not doing much besides managing their in-house proto-museum of cursed tchotchkes and heading barely attended college lectures whose young audience members view them less seriously than the just-released Ghostbusters film. But they’re drawn — and it takes for what feels like forever — to the Pennsylvania case at Judy’s behest, and because of an item there that’s seemingly responsible for all the suddenly-showing-up supernatural problems they can hopefully mitigate. It’s a mirror that has ludicrously been gifted to one of the home’s daughters by her grandfather as a confirmation gift. The Warrens have a decades-old personal connection to it that’s clarified in the film’s cold opening.

These movies’ muted-but-there Christianity-championing and unyielding belief that good will conquer evil ensures that despite their onslaught of creepy-crawly set pieces — which, the more you’ve endured, beg logical questions about the “rules” and motivations these demons abide by — the stakes never feel that high. The very worst things that can happen to a character usually happen to someone in the supporting cast. Last Rites, with an overarchingly optimistic outlook undergirded by its celebrations of tender monogamy and the close-knit family unit, is a hard-to-come-by horror film that doesn’t merely have a happy ending but seems, once it’s met its quota of adequately rattling set pieces, to want to make you feel good.