The creakiness of his walk gives him away. Vahid’s (Vahid Mobasseri) blood turns cold when he hears the prosthetic-limbed man’s (Ebrahim Azizi) off-tempo gait from afar at his mechanic job one evening. Could this guy requesting services be the same government lackey who’d years ago extensively tortured him in prison after he’d righteously fought against workplace abuses?

One of many complications in producer-writer-director Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just an Accident — which was valiantly made, as is common for the filmmaker, without authorization from his home country of Iran — is that Vahid never saw his tormentor’s face while he was incarcerated. He can only go off the sound of his voice and the squeaks and drags of his artificial leg, traumatic noises that accompanied his being hung upside down for days on end to encourage the naming of names and savage beatings that have led to chronic back problems.

Vahid is filled with such rage, and so fixated on the idea of exacting revenge, that the next day he stalks the man, Eghbal, around Tehran for a while before creeping up on him, knocking him out, and stowing him away in a funeral-size box in his van. Vahid’s immediate plans are to bury his one-time captor alive. But Eghbal, while choking on desert dust at his designated murder site, plants seeds of doubt. His amputation scars are supposedly newer than Vahid’s prison stint, and Vahid feels pangs of sympathy when his hastily nabbed victim speaks of an upcoming doctor’s appointment. Ever the ethical kidnapper, Vahid temporarily abandons his plan and begins a quasi-quest around town to check in with those whom Eghbal also tortured to ensure his vengeance is not being misplaced onto an innocent civilian.

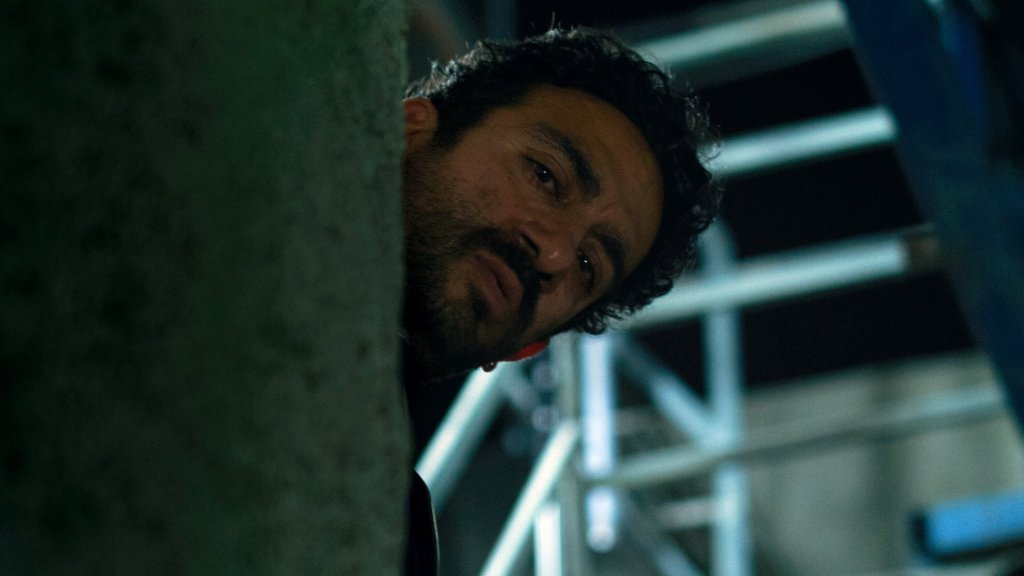

Vahid Mobasseri in It Was Just an Accident. All It Was Just an Accident imagery courtesy of Neon.

Vahid and his revenge-seekers-in-arms’ carefulness is slightly but not tone-upsettingly absurd; humanity remains, with the exception of a bloodlusting wild card in the bunch (Mohamad Ali Elyasmehr), in people with enough reason to have lost touch with it. There’s a tacit consensus that revenge’s instant satisfactions will not be lastingly cathartic. Eghbal’s destructiveness within a brutal, devastating system will not upend it, the chances of getting away with things slim. Amid the uncertainty, Vahid and his frantically gathered associates, in what’s probably the film’s most stupefying gesture, take Eghbal’s heavily pregnant wife to the hospital after they intercept calls from his young daughter. Her mom has passed out in the kitchen, unresponsive to wake-up nudges.

Panahi’s disdain for the Islamic Republic’s cruelty and corruption is central and also oblique. It Was Just an Accident’s contempt manifests less through direct criticism and more by foregrounding the moral heedfulness of its principal characters and the comparative lack in those who’ve psychologically and physically scarred them. Their hesitation bespeaks how violence corrodes in other ways. These people, one of whom refers to his pre-torture wouldn’t-hurt-a-fly disposition, wouldn’t be in their temptation-beckoning position — and seriously considering satiating it — were it not for authoritarianism’s evils. The film’s intense climax shakes with continued uncertainty; its extendedness evokes how elusive closure is even after eye-for-an-eye attempts at resolution have been seen through.

It Was Just an Accident won the Palme d’Or in May. Its premiere marked Panahi’s first time attending the Cannes Film Festival since 2003, when his Crimson Gold was screened and was thereafter forbidden from showings in Iran. Panahi’s continued artistic rebellion against his government has led to arrests, filmmaking bans, and imprisonment, but he’s remained undeterred, sneakily finding new vantage points from which to covertly make movies. It Was Just an Accident’s making followed a successful hunger-strike protestation of another unreasonable sentencing he did not ultimately complete; beyond the tense thrills of its narrative, Panahi’s decision to continue cinematically opposing his country’s censoring authorities rather than momentarily luxuriate in the relief of freedom so soon after his release imbues the movie with momentousness and urgency.

Josh O’Connor and Lily LaTorre in Rebuilding. Photo by Jesse Hope.

I like the boyish Josh O’Connor in taciturn Colorado cowboy mode and less so the frustrating restraint of the movie it services. Rebuilding, writer-director Max Walker-Silverman’s follow-up to 2022’s A Love Song, has the same hard-to-get-over problem the latter had: its maker loves his seen-better-days characters too much. He doesn’t excavate them very deeply because of what seems like a protective fear that the audience will look at them as something other than strong-and-stoic people worthy of admiration — that it will overly complicate the simple-life, Western-aesthetic-inflected lyricism he’s going for. Walker-Silverman is hemmed in by a commitment to vaguely patronizing loveliness.

A Love Song was at least laudably unsentimental. Rebuilding is drippier. It’s plagued with an aggressively somber acoustic Jake Xerxes Fussell and James Elkington score that sounds borrowed from a Subaru commercial, and it’s capped off with an optimistic, community-minded ending that would be more powerful if you knew the characters much more than their hard circumstances and the fortitude shown in the face of them. Rebuilding’s circumstances are certainly harder than they were in A Love Song. O’Connor plays a farmer whose property has been snuffed out by wildfires, and after a period of couch-surfing, he temporarily relocates to a small Federal Emergency Management Agency camp with others who’ve endured the same. (He grows closest to Mali, a sensible, thinly written woman portrayed by Kali Reis who’s been at the site about two months longer than him.)

Walker-Silverman uses the masculine reticence of O’Connor’s character, who barely speaks louder than a whisper, as what feels like an excuse not to get to better know him. His protagonist clings to unrealistic-but-understandable hopes that his ash-dusted property can be saved, has an ex-childhood sweetheart he’s on pretty good terms with (Meghann Fahy), and has a young daughter (Lily LaTorre) with her who wants badly (but, in line with her reserved dad, not too loudly) to spend more time with a father who thinks she doesn’t need him. Walker-Silverman doesn’t shade in those details as much as simply offer them, leaning heavily on his skillful ensemble — which includes an underused Amy Madigan as a grandma character downplaying her ill health — to fill in what’s unscripted.

Rebuilding is naturally best when it forgoes the generic for specificity and unguardedness: a short but efficiently mournful scene where O’Connor’s character and his fellow FEMA campers pine around a picnic table for things like pressed-flower displays, family fiddles, and other soon-to-be-forgotten household ephemera wildfires took from them; a later moment where O’Connor, a rainstorm rattling his color-sapped trailer, finally breaks down. Even the latter emotional fracturing maintains Walker-Silverman’s preferred mode of mutedness, though: O’Connor lets out his heaviest sobs behind his hands despite being alone. That’s more than we get during a funeral scene, where no one sheds a tear. I wanted Walker-Silverman to let his characters cry.