Written, directed by, and starring Cherien Dabis, Palestinian family drama All That’s Left of You states, in so many words, that it doesn’t feel like it can meaningfully tell its central lineage’s story without going back a few generations. “I’m here to tell you who is my son,” the family’s matriarch, Hanan (Dabis), says to an Israeli man she’s sitting across from in a Tel Aviv coffee shop for heartbreaking reasons that will emerge later. “But for you to understand, I must tell you what happened to his grandfather.”

All That’s Left of You’s wrenching, sensitively spun narrative begins in Jaffa in 1948, in the days leading up to Israel’s establishment, and concludes on the long-seized port city’s sunset-lit shores in 2022. In the years between, its never-surnamed family suffers violent displacement (from their native Jaffa to the occupied West Bank); sadistic Israel Defense Forces humiliations that mutate familial dynamics; derailed emergency health care on account of maddeningly restrictive Israeli bureaucracy; and a devastating killing at a protest.

With its story officially commencing with glances of happier times in pre-Israel Jaffa and finding every subsequent tragedy faced related to Palestine’s occupation, Dabis keeps at All That’s Left of You’s forefront an ache for what could have been — how the lives, and the hopes and dreams, of this family might have looked if everything wasn’t contaminated by the omnipresent threats and dangers subjugation makes inescapable. No one in the film is unequivocally portrayed as a victim, though: The clearly rendered personhood of the characters is stained, but not defined, by the evils imposed on them. (Dabis’ decision to cast multiple generations of the renowned Bakri family — all of whose members give wonderful, lived-in performances — contributes to the movie’s poignancy and sense of resilience.)

Dabis — whose directing work had not, before All That’s Left of You’s release, so directly dealt with the Nakba — didn’t come of age in the country from which her father was exiled in 1967. But though the Ohio-raised Palestinian-Jordanian filmmaker was largely physically removed from the day-to-day realities of life under occupation, she still grew up seeing the existential ramifications of her father’s expulsion, how he’d be hurt and harassed at IDF checkpoints on the occasions that they’d visit home, and the appallingly dehumanizing way Palestinians were portrayed in Western media.

A project Dabis has described as a decade in the making, All That’s Left of You vigorously but tenderly rebukes that ongoing dehumanization, its scale deepening its emotional contours and intimacy. Because the start of its production coincided with the genocidal aftermath of the Oct. 7, 2023, attacks, the film took on additional meaning for Dabis and her collaborators as they made it. “We were so grateful to have the movie as a vehicle, a container for all of the things we were feeling, given everything we were watching happen,” Dabis recounted to Rough Cut Film last year. “The movie really did become a container of our grief and our love and our compassion.”

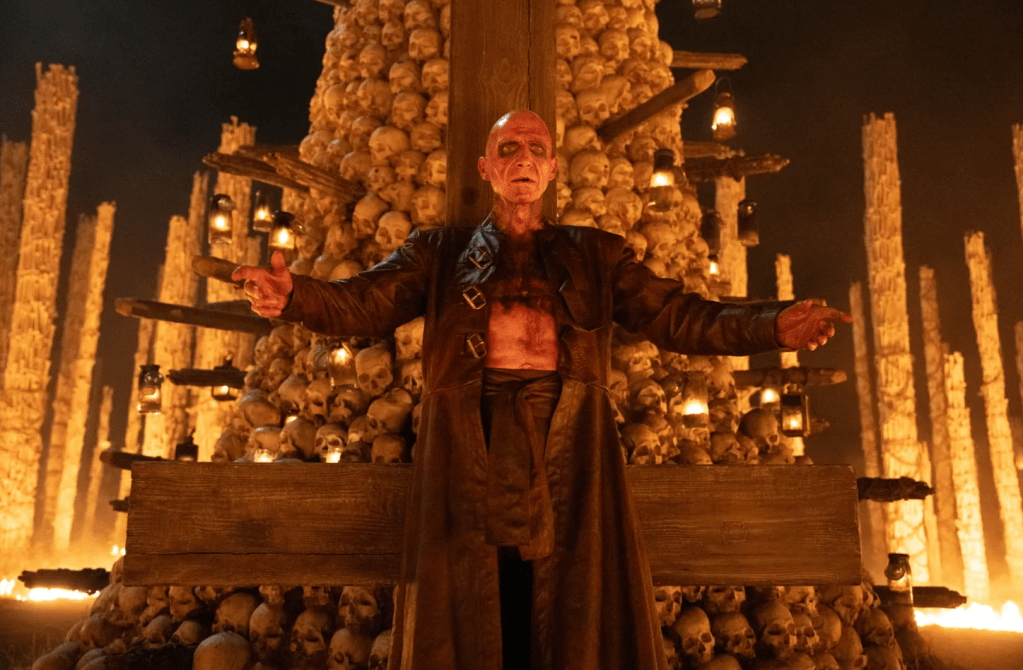

Ralph Fiennes in 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple. Photo by Miya Mizuno/Columbia Pictures. All That’s Left of You photo courtesy of Watermelon Pictures.

How Nia DaCosta follows up her elegantly frosty adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda typifies the admirable “I want to try everything” principle animating her career so far. Less than three months after the latter film’s release, the 36-year-old filmmaker — who has behind her a scrappy crime drama, a superhero movie, and a chilly urban legend-rooted horror film — is at the helm of 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, a sequel to the recently resurrected zombie-apocalypse franchise that began its long lurch forward in 2002 with 28 Days Later.

Last June’s 28 Years Later offered a surprisingly touching coming-of-age narrative. It narrowed in on a saucer-eyed 12-year-old named Spike (Alfie Williams) living in a high-functioning waterfront village with survivors that included his superstar-hunter father (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) and mysterious illness-afflicted mother (Jodie Comer). Especially once you get to its nostalgia-satiating cliffhanger, The Bone Temple comes across as a movie-length segue for what’s being positioned as a trilogy. It finds Spike, cleaved from the forces keeping him at home, practically forced into a gang. It’s led by a rotten-toothed man who calls himself Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal (Jack O’Connell); his faithful flock is made up of presumably orphaned teenagers who wear complementarily rumpled track suits and stringy beach-bum-blonde wigs. They enthusiastically do whatever their leader says, which mostly consists of plundering the homes of and then sadomasochistically torturing to death those living inside. (A stomach-twisting example arrives early on in The Bone Temple; impressive about DaCosta’s direction is how viscerally upsetting and no-holds-barred the violence can be, even by zombie-movie standards.)

The movie’s B plot, which eventually braids with the A, is comparatively a breezy stroll on the beach. A self-protectively iodine-slathered doctor character from the last film who’d helped Spike and his mother, Ian (Ralph Fiennes), strikes up an unlikely friendship with a decapitation-prone zombie with a professional wrestler’s body (Chi Lewis-Parry). Ian gives the long-haired colossus virus symptom-palliating morphine that, in a matter of seconds, turns him into a gentle giant — an on-the-nose but pretty effective way of further facilitating the movie’s obvious point that, even in a landscape swarming with the brain-slurping walking dead, the true monstrousness will always be found in power-mad humans who have the ability to know better.

The Bone Temple doesn’t move the franchise’s narrative forward that much. It’s a horrifying adventure that aggravates the already stacked traumas inflicted on Spike, who’s unfortunately here reduced into a scared-senseless character who understandably can do little else but whimper and plead, and a gory mechanism to introduce and dispense with characters ahead of the reborn franchise’s third part. What it’s best at is serving as a stage for the tiara’d O’Connell’s sleazy, squirmily fun-to-watch theatrics, which will probably land him on plenty of future “best movie villain”-style lists. The Bone Temple doesn’t, beyond the sartorial similarities, get into the Jimmy Savile of it all; I guess it has, in its danger-ridden setting, other things to worry about.